by Admin

The Power Of The Intl API: A Definitive Guide To Browser-Native Internationalization

The Power Of The <code>Intl</code> API: A Definitive Guide To Browser-Native Internationalization The Power Of The <code>Intl</code> API: A Definitive Guide To Browser-Native Internationalization Fuqiao Xue 2025-08-08T10:00:00+00:00 2025-08-13T15:04:28+00:00 It’s a common misconception that internationalization (i18n) is simply about translating text. While crucial, translation is merely […]

Accessibility

by Admin

Automating Design Systems: Tips And Resources For Getting Started

Automating Design Systems: Tips And Resources For Getting Started Automating Design Systems: Tips And Resources For Getting Started Joas Pambou 2025-08-06T10:00:00+00:00 2025-08-07T14:02:50+00:00 A design system is more than just a set of colors and buttons. It’s a shared language that helps designers and developers build […]

Accessibility

by Admin

UX Job Interview Helpers

UX Job Interview Helpers UX Job Interview Helpers Vitaly Friedman 2025-08-05T13:00:00+00:00 2025-08-07T14:02:50+00:00 When talking about job interviews for a UX position, we often discuss how to leave an incredible impression and how to negotiate the right salary. But it’s only one part of the story. […]

Accessibility

Designing For Neurodiversity

by Admin

Designing For Neurodiversity Designing For Neurodiversity Vitaly Friedman 2025-06-02T08:00:00+00:00 2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00 This article is sponsored by TetraLogical Neurodivergent needs are often considered as an edge case that doesn’t fit into common user journeys or flows. Neurodiversity tends to get overlooked in the design process. Or it […]

Accessibility

Designing For Neurodiversity

Vitaly Friedman 2025-06-02T08:00:00+00:00

2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00

This article is sponsored by TetraLogical

Neurodivergent needs are often considered as an edge case that doesn’t fit into common user journeys or flows. Neurodiversity tends to get overlooked in the design process. Or it is tackled late in the process, and only if there is enough time.

But people aren’t edge cases. Every person is just a different person, performing tasks and navigating the web in a different way. So how can we design better, more inclusive experiences that cater to different needs and, ultimately, benefit everyone? Let’s take a closer look.

Neurodiversity Or Neurodivergent?

There is quite a bit of confusion about both terms on the web. Different people think and experience the world differently, and neurodiversity sees differences as natural variations, not deficits. It distinguishes between neurotypical and neurodivergent people.

- Neurotypical people see the world in a “typical” and widely perceived as expected way.

- Neurodivergent people experience the world differently, for example, people with ADHD, dyslexia, dyscalculia, synesthesia, and hyperlexia.

According to various sources, around 15–40% of the population has neurodivergent traits. These traits can be innate (e.g., autism) or acquired (e.g., trauma). But they are always on a spectrum, and vary a lot. A person with autism is not neurodiverse — they are neurodivergent.

One of the main strengths of neurodivergent people is how imaginative and creative they are, coming up with out-of-the-box ideas quickly. With exceptional levels of attention, strong long-term memory, a unique perspective, unbeatable accuracy, and a strong sense of justice and fairness.

Being different in a world that, to some degree, still doesn’t accept these differences is exhausting. So unsurprisingly, neurodivergent people often bring along determination, resilience, and high levels of empathy.

Design With People, Not For Them

As a designer, I often see myself as a path-maker. I’m designing reliable paths for people to navigate to their goals comfortably. Without being blocked. Or confused. Or locked out.

That means respecting the simple fact that people’s needs, tasks, and user journeys are all different, and that they evolve over time. And: most importantly, it means considering them very early in the process.

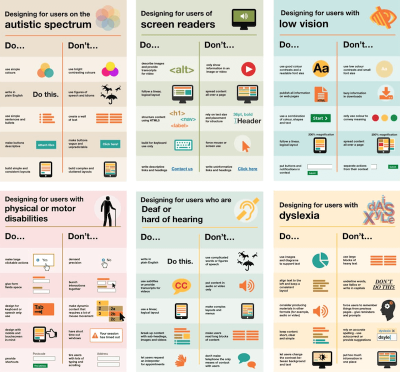

Better accessibility is better for everyone. Instead of making decisions that need to be reverted or refined to be compliant, we can bring a diverse group of people — with accessibility needs, with neurodiversity, frequent and infrequent users, experts, newcomers — in the process, and design with them, rather than for them.

Neurodiversity & Inclusive Design Resources

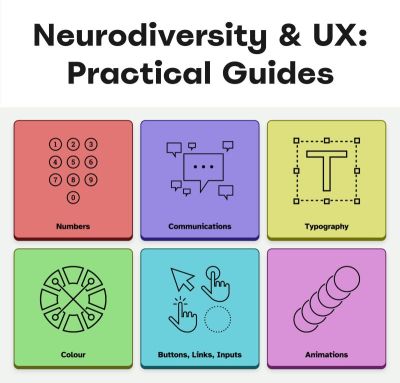

A wonderful resource that helps us design for cognitive accessibility is Stéphanie Walter’s Neurodiversity and UX toolkit. It includes practical guidelines, tools, and resources to better understand and design for dyslexia, dyscalculia, autism, and ADHD.

Another fantastic resource is Will Soward’s Neurodiversity Design System. It combines neurodiversity and user experience design into a set of design standards and principles that you can use to design accessible learning interfaces.

Last but not least, I’ve been putting together a few summaries about neurodiversity and inclusive design over the last few years, so you might find them helpful, too:

- ADHD

- Autism

- Children

- Colorblindness

- Deafness

- Dyscalculia

- Dyslexia

- Legibility

- Left-Handed Users

- Mental Health

- Motivation

- Older Adults

- Screen Readers

- Teenagers

A huge thank-you to everyone who has been writing, speaking, and sharing articles, resources, and toolkits on designing for diversity. The topic is often forgotten and overlooked, but it has an incredible impact. 👏🏼👏🏽👏🏾

(vf, il, yk)

by Admin

Reliably Detecting Third-Party Cookie Blocking In 2025

Reliably Detecting Third-Party Cookie Blocking In 2025 Reliably Detecting Third-Party Cookie Blocking In 2025 Mikhail Prosmitskiy 2025-05-28T10:00:00+00:00 2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00 The web is beginning to part ways with third-party cookies, a technology it once heavily relied on. Introduced in 1994 by Netscape to support features like virtual shopping carts, cookies have […]

Accessibility

Reliably Detecting Third-Party Cookie Blocking In 2025

Mikhail Prosmitskiy 2025-05-28T10:00:00+00:00

2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00

The web is beginning to part ways with third-party cookies, a technology it once heavily relied on. Introduced in 1994 by Netscape to support features like virtual shopping carts, cookies have long been a staple of web functionality. However, concerns over privacy and security have led to a concerted effort to eliminate them. The World Wide Web Consortium Technical Architecture Group (W3C TAG) has been vocal in advocating for the complete removal of third-party cookies from the web platform.

Major browsers (Chrome, Safari, Firefox, and Edge) are responding by phasing them out, though the transition is gradual. While this shift enhances user privacy, it also disrupts legitimate functionalities that rely on third-party cookies, such as single sign-on (SSO), fraud prevention, and embedded services. And because there is still no universal ban in place and many essential web features continue to depend on these cookies, developers must detect when third-party cookies are blocked so that applications can respond gracefully.

Don’t Let Silent Failures Win: Why Cookie Detection Still Matters

Yes, the ideal solution is to move away from third-party cookies altogether and redesign our integrations using privacy-first, purpose-built alternatives as soon as possible. But in reality, that migration can take months or even years, especially for legacy systems or third-party vendors. Meanwhile, users are already browsing with third-party cookies disabled and often have no idea that anything is missing.

Imagine a travel booking platform that embeds an iframe from a third-party partner to display live train or flight schedules. This embedded service uses a cookie on its own domain to authenticate the user and personalize content, like showing saved trips or loyalty rewards. But when the browser blocks third-party cookies, the iframe cannot access that data. Instead of a seamless experience, the user sees an error, a blank screen, or a login prompt that doesn’t work.

And while your team is still planning a long-term integration overhaul, this is already happening to real users. They don’t see a cookie policy; they just see a broken booking flow.

Detecting third-party cookie blocking isn’t just good technical hygiene but a frontline defense for user experience.

“

Why It’s Hard To Tell If Third-Party Cookies Are Blocked

Detecting whether third-party cookies are supported isn’t as simple as calling navigator.cookieEnabled. Even a well-intentioned check like this one may look safe, but it still won’t tell you what you actually need to know:

// DOES NOT detect third-party cookie blocking

function areCookiesEnabled() {

if (navigator.cookieEnabled === false) {

return false;

}

try {

document.cookie = "test_cookie=1; SameSite=None; Secure";

const hasCookie = document.cookie.includes("test_cookie=1");

document.cookie = "test_cookie=; Max-Age=0; SameSite=None; Secure";

return hasCookie;

} catch (e) {

return false;

}

}

This function only confirms that cookies work in the current (first-party) context. It says nothing about third-party scenarios, like an iframe on another domain. Worse, it’s misleading: in some browsers, navigator.cookieEnabled may still return true inside a third-party iframe even when cookies are blocked. Others might behave differently, leading to inconsistent and unreliable detection.

These cross-browser inconsistencies — combined with the limitations of document.cookie — make it clear that there is no shortcut for detection. To truly detect third-party cookie blocking, we need to understand how different browsers actually behave in embedded third-party contexts.

How Modern Browsers Handle Third-Party Cookies

The behavior of modern browsers directly affects which detection methods will work and which ones silently fail.

Safari: Full Third-Party Cookie Blocking

Since version 13.1, Safari blocks all third-party cookies by default, with no exceptions, even if the user previously interacted with the embedded domain. This policy is part of Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP).

For embedded content (such as an SSO iframe) that requires cookie access, Safari exposes the Storage Access API, which requires a user gesture to grant storage permission. As a result, a test for third-party cookie support will nearly always fail in Safari unless the iframe explicitly requests access via this API.

Firefox: Cookie Partitioning By Design

Firefox’s Total Cookie Protection isolates cookies on a per-site basis. Third-party cookies can still be set and read, but they are partitioned by the top-level site, meaning a cookie set by the same third-party on siteA.com and siteB.com is stored separately and cannot be shared.

As of Firefox 102, this behavior is enabled by default in the Standard (default) mode of Enhanced Tracking Protection. Unlike the Strict mode — which blocks third-party cookies entirely, similar to Safari — the Standard mode does not block them outright. Instead, it neutralizes their tracking capability by isolating them per site.

As a result, even if a test shows that a third-party cookie was successfully set, it may be useless for cross-site logins or shared sessions due to this partitioning. Detection logic needs to account for that.

Chrome: From Deprecation Plans To Privacy Sandbox (And Industry Pushback)

Chromium-based browsers still allow third-party cookies by default — but the story is changing. Starting with Chrome 80, third-party cookies must be explicitly marked with SameSite=None; Secure, or they will be rejected.

In January 2020, Google announced their intention to phase out third-party cookies by 2022. However, the timeline was updated multiple times, first in June 2021 when the company pushed the rollout to begin in mid-2023 and conclude by the end of that year. Additional postponements followed in July 2022, December 2023, and April 2024.

In July 2024, Google has clarified that there is no plan to unilaterally deprecate third-party cookies or force users into a new model without consent. Instead, Chrome is shifting to a user-choice interface that will allow individuals to decide whether to block or allow third-party cookies globally.

This change was influenced in part by substantial pushback from the advertising industry, as well as ongoing regulatory oversight, including scrutiny by the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) into Google’s Privacy Sandbox initiative. The CMA confirmed in a 2025 update that there is no intention to force a deprecation or trigger automatic prompts for cookie blocking.

As for now, third-party cookies remain enabled by default in Chrome. The new user-facing controls and the broader Privacy Sandbox ecosystem are still in various stages of experimentation and limited rollout.

Edge (Chromium-Based): Tracker-Focused Blocking With User Configurability

Edge (which is a Chromium-based browser) shares Chrome’s handling of third-party cookies, including the SameSite=None; Secure requirement. Additionally, Edge introduces Tracking Prevention modes: Basic, Balanced (default), and Strict. In Balanced mode, it blocks known third-party trackers using Microsoft’s maintained list but allows many third-party cookies that are not classified as trackers. Strict mode blocks more resource loads than Balanced, which may result in some websites not behaving as expected.

Other Browsers: What About Them?

Privacy-focused browsers, like Brave, block third-party cookies by default as part of their strong anti-tracking stance.

Internet Explorer (IE) 11 allowed third-party cookies depending on user privacy settings and the presence of Platform for Privacy Preferences (P3P) headers. However, IE usage is now negligible. Notably, the default “Medium” privacy setting in IE could block third-party cookies unless a valid P3P policy was present.

Older versions of Safari had partial third-party cookie restrictions (such as “Allow from websites I visit”), but, as mentioned before, this was replaced with full blocking via ITP.

As of 2025, all major browsers either block or isolate third-party cookies by default, with the exception of Chrome, which still allows them in standard browsing mode pending the rollout of its new user-choice model.

To account for these variations, your detection strategy must be grounded in real-world testing — specifically by reproducing a genuine third-party context such as loading your script within an iframe on a cross-origin domain — rather than relying on browser names or versions.

Overview Of Detection Techniques

Over the years, many techniques have been used to detect third-party cookie blocking. Most are unreliable or obsolete. Here’s a quick walkthrough of what doesn’t work (and why) and what does.

Basic JavaScript API Checks (Misleading)

As mentioned earlier, the navigator.cookieEnabled or setting document.cookie on the main page doesn’t reflect cross-site cookie status:

- In third-party iframes,

navigator.cookieEnabledoften returnstrueeven when cookies are blocked. - Setting

document.cookiein the parent doesn’t test the third-party context.

These checks are first-party only. Avoid using them for detection.

Storage Hacks Via localStorage (Obsolete)

Previously, some developers inferred cookie support by checking if window.localStorage worked inside a third-party iframe — which is especially useful against older Safari versions that blocked all third-party storage.

Modern browsers often allow localStorage even when cookies are blocked. This leads to false positives and is no longer reliable.

Server-Assisted Cookie Probe (Heavyweight)

One classic method involves setting a cookie from a third-party domain via HTTP and then checking if it comes back:

- Load a script/image from a third-party server that sets a cookie.

- Immediately load another resource, and the server checks whether the cookie was sent.

This works, but it:

- Requires custom server-side logic,

- Depends on HTTP caching, response headers, and cookie attributes (

SameSite=None; Secure), and - Adds development and infrastructure complexity.

While this is technically valid, it is not suitable for a front-end-only approach, which is our focus here.

Storage Access API (Supplemental Signal)

The document.hasStorageAccess() method allows embedded third-party content to check if it has access to unpartitioned cookies:

- Chrome

SupportshasStorageAccess()andrequestStorageAccess()starting from version 119. Additionally,hasUnpartitionedCookieAccess()is available as an alias forhasStorageAccess()from version 125 onwards. - Firefox

Supports bothhasStorageAccess()andrequestStorageAccess()methods. - Safari

Supports the Storage Access API. However, access must always be triggered by a user interaction. For example, even callingrequestStorageAccess()without a direct user gesture (like a click) is ignored.

Chrome and Firefox also support the API, and in those browsers, it may work automatically or based on browser heuristics or site engagement.

This API is particularly useful for detecting scenarios where cookies are present but partitioned (e.g., Firefox’s Total Cookie Protection), as it helps determine if the iframe has unrestricted cookie access. But for now, it’s still best used as a supplemental signal, rather than a standalone check.

iFrame + postMessage (Best Practice)

Despite the existence of the Storage Access API, at the time of writing, this remains the most reliable and browser-compatible method:

- Embed a hidden iframe from a third-party domain.

- Inside the iframe, attempt to set a test cookie.

- Use

window.postMessageto report success or failure to the parent.

This approach works across all major browsers (when properly configured), requires no server (kind of, more on that next), and simulates a real-world third-party scenario.

We’ll implement this step-by-step next.

Bonus: Sec-Fetch-Storage-Access

Chrome (starting in version 133) is introducing Sec-Fetch-Storage-Access, an HTTP request header sent with cross-site requests to indicate whether the iframe has access to unpartitioned cookies. This header is only visible to servers and cannot be accessed via JavaScript. It’s useful for back-end analytics but not applicable for client-side cookie detection.

As of May 2025, this feature is only implemented in Chrome and is not supported by other browsers. However, it’s still good to know that it’s part of the evolving ecosystem.

Step-by-Step: Detecting Third-Party Cookies Via iFrame

So, what did I mean when I said that the last method we looked at “requires no server”? While this method doesn’t require any back-end logic (like server-set cookies or response inspection), it does require access to a separate domain — or at least a cross-site subdomain — to simulate a third-party environment. This means the following:

- You must serve the test page from a different domain or public subdomain, e.g.,

example.comandcookietest.example.com, - The domain needs HTTPS (for

SameSite=None; Securecookies to work), and - You’ll need to host a simple static file (the test page), even if no server code is involved.

Once that’s set up, the rest of the logic is fully client-side.

Step 1: Create A Cookie Test Page (On A Third-Party Domain)

Minimal version (e.g., https://cookietest.example.com/cookie-check.html):

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<script>

document.cookie = "thirdparty_test=1; SameSite=None; Secure; Path=/;";

const cookieFound = document.cookie.includes("thirdparty_test=1");

const sendResult = (status) => window.parent?.postMessage(status, "*");

if (cookieFound && document.hasStorageAccess instanceof Function) {

document.hasStorageAccess().then((hasAccess) => {

sendResult(hasAccess ? "TP_COOKIE_SUPPORTED" : "TP_COOKIE_BLOCKED");

}).catch(() => sendResult("TP_COOKIE_BLOCKED"));

} else {

sendResult(cookieFound ? "TP_COOKIE_SUPPORTED" : "TP_COOKIE_BLOCKED");

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

Make sure the page is served over HTTPS, and the cookie uses SameSite=None; Secure. Without these attributes, modern browsers will silently reject it.

Step 2: Embed The iFrame And Listen For The Result

On your main page:

function checkThirdPartyCookies() {

return new Promise((resolve) => {

const iframe = document.createElement('iframe');

iframe.style.display = 'none';

iframe.src = "https://cookietest.example.com/cookie-check.html"; // your subdomain

document.body.appendChild(iframe);

let resolved = false;

const cleanup = (result, timedOut = false) => {

if (resolved) return;

resolved = true;

window.removeEventListener('message', onMessage);

iframe.remove();

resolve({ thirdPartyCookiesEnabled: result, timedOut });

};

const onMessage = (event) => {

if (["TP_COOKIE_SUPPORTED", "TP_COOKIE_BLOCKED"].includes(event.data)) {

cleanup(event.data === "TP_COOKIE_SUPPORTED", false);

}

};

window.addEventListener('message', onMessage);

setTimeout(() => cleanup(false, true), 1000);

});

}

Example usage:

checkThirdPartyCookies().then(({ thirdPartyCookiesEnabled, timedOut }) => {

if (!thirdPartyCookiesEnabled) {

someCookiesBlockedCallback(); // Third-party cookies are blocked.

if (timedOut) {

// No response received (iframe possibly blocked).

// Optional fallback UX goes here.

someCookiesBlockedTimeoutCallback();

};

}

});

Step 3: Enhance Detection With The Storage Access API

In Safari, even when third-party cookies are blocked, users can manually grant access through the Storage Access API — but only in response to a user gesture.

Here’s how you could implement that in your iframe test page:

<button id="enable-cookies">This embedded content requires cookie access. Click below to continue.</button>

<script>

document.getElementById('enable-cookies')?.addEventListener('click', async () => {

if (document.requestStorageAccess && typeof document.requestStorageAccess === 'function') {

try {

const granted = await document.requestStorageAccess();

if (granted !== false) {

window.parent.postMessage("TP_STORAGE_ACCESS_GRANTED", "*");

} else {

window.parent.postMessage("TP_STORAGE_ACCESS_DENIED", "*");

}

} catch (e) {

window.parent.postMessage("TP_STORAGE_ACCESS_FAILED", "*");

}

}

});

</script>

Then, on the parent page, you can listen for this message and retry detection if needed:

// Inside the same `onMessage` listener from before:

if (event.data === "TP_STORAGE_ACCESS_GRANTED") {

// Optionally: retry the cookie test, or reload iframe logic

checkThirdPartyCookies().then(handleResultAgain);

}

(Bonus) A Purely Client-Side Fallback (Not Perfect, But Sometimes Necessary)

In some situations, you might not have access to a second domain or can’t host third-party content under your control. That makes the iframe method unfeasible.

When that’s the case, your best option is to combine multiple signals — basic cookie checks, hasStorageAccess(), localStorage fallbacks, and maybe even passive indicators like load failures or timeouts — to infer whether third-party cookies are likely blocked.

The important caveat: This will never be 100% accurate. But, in constrained environments, “better something than nothing” may still improve the UX.

Here’s a basic example:

async function inferCookieSupportFallback() {

let hasCookieAPI = navigator.cookieEnabled;

let canSetCookie = false;

let hasStorageAccess = false;

try {

document.cookie = "testfallback=1; SameSite=None; Secure; Path=/;";

canSetCookie = document.cookie.includes("test_fallback=1");

document.cookie = "test_fallback=; Max-Age=0; Path=/;";

} catch (_) {

canSetCookie = false;

}

if (typeof document.hasStorageAccess === "function") {

try {

hasStorageAccess = await document.hasStorageAccess();

} catch (_) {}

}

return {

inferredThirdPartyCookies: hasCookieAPI && canSetCookie && hasStorageAccess,

raw: { hasCookieAPI, canSetCookie, hasStorageAccess }

};

}

Example usage:

inferCookieSupportFallback().then(({ inferredThirdPartyCookies }) => {

if (inferredThirdPartyCookies) {

console.log("Cookies likely supported. Likely, yes.");

} else {

console.warn("Cookies may be blocked or partitioned.");

// You could inform the user or adjust behavior accordingly

}

});

Use this fallback when:

- You’re building a JavaScript-only widget embedded on unknown sites,

- You don’t control a second domain (or the team refuses to add one), or

- You just need some visibility into user-side behavior (e.g., debugging UX issues).

Don’t rely on it for security-critical logic (e.g., auth gating)! But it may help tailor the user experience, surface warnings, or decide whether to attempt a fallback SSO flow. Again, it’s better to have something rather than nothing.

Fallback Strategies When Third-Party Cookies Are Blocked

Detecting blocked cookies is only half the battle. Once you know they’re unavailable, what can you do? Here are some practical options that might be useful for you:

Redirect-Based Flows

For auth-related flows, switch from embedded iframes to top-level redirects. Let the user authenticate directly on the identity provider’s site, then redirect back. It works in all browsers, but the UX might be less seamless.

Request Storage Access

Prompt the user using requestStorageAccess() after a clear UI gesture (Safari requires this). Use this to re-enable cookies without leaving the page.

Token-Based Communication

Pass session info directly from parent to iframe via:

postMessage(with requiredorigin);- Query params (e.g., signed JWT in iframe URL).

This avoids reliance on cookies entirely but requires coordination between both sides:

// Parent

const iframe = document.getElementById('my-iframe');

iframe.onload = () => {

const token = getAccessTokenSomehow(); // JWT or anything else

iframe.contentWindow.postMessage(

{ type: 'AUTH_TOKEN', token },

'https://iframe.example.com' // Set the correct origin!

);

};

// iframe

window.addEventListener('message', (event) => {

if (event.origin !== 'https://parent.example.com') return;

const { type, token } = event.data;

if (type === 'AUTH_TOKEN') {

validateAndUseToken(token); // process JWT, init session, etc

}

});

Partitioned Cookies (CHIPS)

Chrome (since version 114) and other Chromium-based browsers now support cookies with the Partitioned attribute (known as CHIPS), allowing per-top-site cookie isolation. This is useful for widgets like chat or embedded forms where cross-site identity isn’t needed.

Note: Firefox and Safari don’t support the

Partitionedcookie attribute. Firefox enforces cookie partitioning by default using a different mechanism (Total Cookie Protection), while Safari blocks third-party cookies entirely.

But be careful, as they are treated as “blocked” by basic detection. Refine your logic if needed.

Final Thought: Transparency, Transition, And The Path Forward

Third-party cookies are disappearing, albeit gradually and unevenly. Until the transition is complete, your job as a developer is to bridge the gap between technical limitations and real-world user experience. That means:

- Keep an eye on the standards.

APIs like FedCM and Privacy Sandbox features (Topics, Attribution Reporting, Fenced Frames) are reshaping how we handle identity and analytics without relying on cross-site cookies. - Combine detection with graceful fallback.

Whether it’s offering a redirect flow, usingrequestStorageAccess(), or falling back to token-based messaging — every small UX improvement adds up. - Inform your users.

Users shouldn’t be left wondering why something worked in one browser but silently broke in another. Don’t let them feel like they did something wrong — just help them move forward. A clear, friendly message can prevent this confusion.

The good news? You don’t need a perfect solution today, just a resilient one. By detecting issues early and handling them thoughtfully, you protect both your users and your future architecture, one cookie-less browser at a time.

And as seen with Chrome’s pivot away from automatic deprecation, the transition is not always linear. Industry feedback, regulatory oversight, and evolving technical realities continue to shape the time and the solutions.

And don’t forget: having something is better than nothing.

(yk)

by Admin

Data Vs. Findings Vs. Insights In UX

Data Vs. Findings Vs. Insights In UX Data Vs. Findings Vs. Insights In UX Vitaly Friedman 2025-05-27T13:00:00+00:00 2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00 In many companies, data, findings, and insights are all used interchangeably. Slack conversations circle around convincing data points, statistically significant findings, reliable insights, and emerging trends. Unsurprisingly, […]

Accessibility

Data Vs. Findings Vs. Insights In UX

Vitaly Friedman 2025-05-27T13:00:00+00:00

2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00

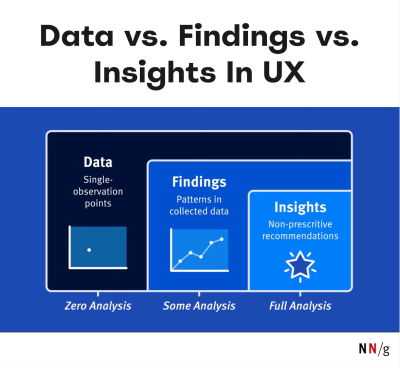

In many companies, data, findings, and insights are all used interchangeably. Slack conversations circle around convincing data points, statistically significant findings, reliable insights, and emerging trends. Unsurprisingly, conversations often mistake sporadic observations for consistent patterns.

But how impactful is the weight that each of them carries? And how do we turn raw data into meaningful insights to make better decisions? Well, let’s find out.

Why It All Matters

At first, it may seem that the differences are very nuanced and merely technical. But when we review inputs and communicate the outcomes of our UX work, we need to be careful not to conflate terminology — to avoid wrong assumptions, wrong conclusions, and early dismissals.

When strong recommendations and bold statements emerge in a big meeting, inevitably, there will be people questioning the decision-making process. More often than not, they will be the loudest voices in the room, often with their own agenda and priorities that they are trying to protect.

As UX designers, we need to be prepared for it. The last thing we want is to have a weak line of thinking, easily dismantled under the premise of “weak research”, “unreliable findings”, “poor choice of users” — and hence dismissed straight away.

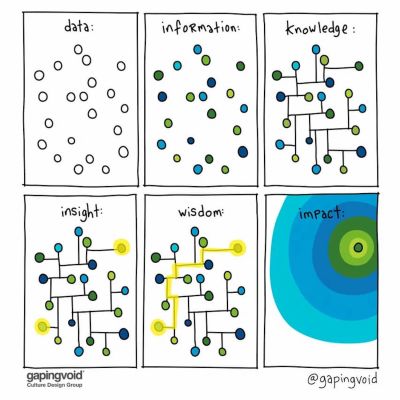

Data ≠ Findings ≠ Insights

People with different roles — analysts, data scientists, researchers, strategists — often rely on fine distinctions to make their decisions. The general difference is easy to put together:

- Data is raw observations (logs, notes, survey answers) (what was recorded).

- Findings describe emerging patterns in data but aren’t actionable (what happened).

- Insights are business opportunities (what happened + why + so what).

- Hindsights are reflections of past actions and outcomes (what we learned in previous work).

- Foresights are informed projections, insights with extrapolation (what could happen next).

Here’s what it then looks like in real life:

- Data ↓

Six users were looking for ”Money transfer” in “Payments”, and 4 users discovered the feature in their personal dashboard. - Finding ↓

60% of users struggled to find the “Money transfer” feature on a dashboard, often confusing it with the “Payments” section. - Insight ↓

Navigation doesn’t match users’ mental models for money transfers, causing confusion and delays. We recommend renaming sections or reorganizing the dashboard to prioritize “Transfer Money”. It could make task completion more intuitive and efficient. - Hindsight ↓

After renaming the section to “Transfer Money” and moving it to the main dashboard, task success increased by 12%. User confusion dropped in follow-up tests. It proved to be an effective solution. - Foresight ↓

As our financial products become more complex, users will expect simpler task-oriented navigation (e.g., “Send Money”, “Pay Bills“) instead of categories like “Payments”. We should evolve the dashboard towards action-driven IA to meet user expectations.

Only insights create understanding and drive strategy. Foresights shape strategy, too, but are always shaped by bets and assumptions. So, unsurprisingly, stakeholders are interested in insights, not findings. They rarely need to dive into raw data points. But often, they do want to make sure that findings are reliable.

That’s when, eventually, the big question about statistical significance comes along. And that’s when ideas and recommendations often get dismissed without a chance to be explored or explained.

But Is It Statistically Significant?

Now, for UX designers, that’s an incredibly difficult question to answer. As Nikki Anderson pointed out, statistical significance was never designed for qualitative research. And with UX work, we’re not trying to publish academic research or prove universal truths.

What we are trying to do is reach theoretical saturation, the point where additional research doesn’t give us new insights. Research isn’t about proving something is true. It’s about preventing costly mistakes before they happen.

Here are some useful talking points to handle the question:

- Five users per segment often surface major issues, and 10–15 users per segment usually reach saturation. If we’re still getting new insights after that, our scope is too broad.

- “If five people hit the same pothole and wreck their car, how many more do you need before fixing the road?”

- “If three enterprise customers say onboarding is confusing, that’s a churn risk.”

- “If two usability tests expose a checkout issue, that’s abandoned revenue.”

- “If one customer interview reveals a security concern, that’s a crisis waiting to happen.”

- “How many user complaints exactly do we need to take this seriously?”

- “How much revenue exactly are we willing to lose before fixing this issue?”

And: it might not be necessary to focus on the number of participants, but instead, argue about users consistently struggling with a feature, mismatch of expectations, and a clear pattern emerging around a particular pain point.

How To Turn Findings Into Insights

Once we notice patterns emerging, we need to turn them into actionable recommendations. Surprisingly, this isn’t always easy — we need to avoid easy guesses and assumptions as far as possible, as they will invite wrong conclusions.

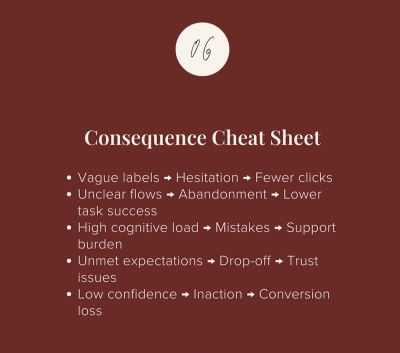

To do that, you can rely on a very simple but effective framework to turn findings into insights: What Happened + Why + So What:

- “What happened” covers observed behavior and patterns.

- “Why” includes beliefs, expectations, or triggers.

- “So What” addresses impact, risk, and business opportunity.

To better assess the “so what” part, we should pay close attention to the impact of what we have noticed on desired business outcomes. It can be anything from high-impact blockers and confusion to hesitation and inaction.

I can wholeheartedly recommend exploring Findings → Insights Cheatsheet in Nikki Anderson’s wonderful slide deck, which has examples and prompts to use to turn findings into insights.

Stop Sharing Findings — Deliver Insights

When presenting the outcomes of your UX work, focus on actionable recommendations and business opportunities rather than patterns that emerged during testing.

To me, it’s all about telling a good damn story. Memorable, impactful, feasible, and convincing. Paint the picture of what the future could look like and the difference it would produce. That’s where the biggest impact of UX work emerges.

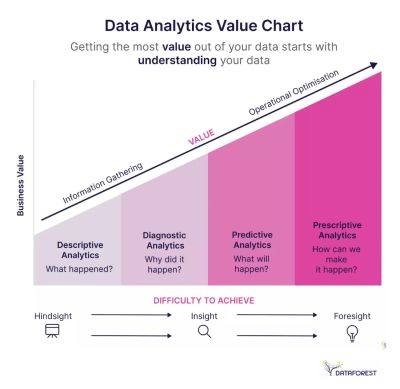

How To Measure UX And Design Impact

Meet Measure UX & Design Impact (8h), a practical guide for designers and UX leads to shape, measure, and explain your incredible UX impact on business. Recorded and updated by Vitaly Friedman. Use the friendly code 🎟 IMPACT to save 20% off today. Jump to the details.

Video + UX Training

$ 495.00 $ 799.00

Get Video + UX Training

25 video lessons (8h) + Live UX Training.

100 days money-back-guarantee.

Video only

$ 250.00$ 395.00

25 video lessons (8h). Updated yearly.

Also available as a UX Bundle with 2 video courses.

Further Reading on Smashing Magazine

- “The Human Element: Using Research And Psychology To Elevate Data Storytelling,” Victor Yocco & Angelica Lo Duca

- “Integrations: From Simple Data Transfer To Modern Composable Architectures,” Edoardo Dusi

- “Scaling Success: Key Insights And Practical Takeaways,” Addy Osmani

- “Embracing Introversion In UX,” Victor Yocco

(mrn, yk)

by Admin

Design System In 90 Days

Design System In 90 Days Design System In 90 Days Vitaly Friedman 2025-05-19T10:00:00+00:00 2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00 So we want to set up a new design system for your product. How do we get it up and running from scratch? Do we start with key stakeholders, UI audits, […]

Accessibility

Design System In 90 Days

Vitaly Friedman 2025-05-19T10:00:00+00:00

2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00

So we want to set up a new design system for your product. How do we get it up and running from scratch? Do we start with key stakeholders, UI audits, or naming conventions? And what are some of the critical conversations we need to have early to avoid problems down the line?

Fortunately, there are a few useful little helpers to get started — and they are the ones I tend to rely on quite a bit when initiating any design system projects.

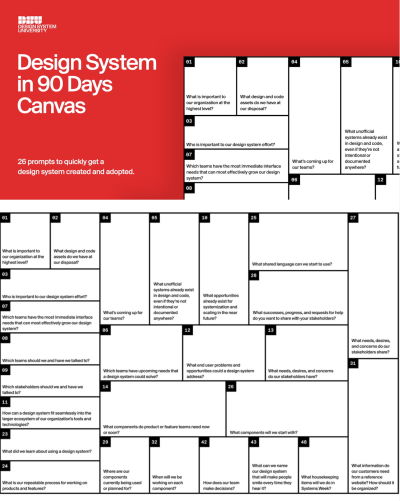

Design System In 90 Days Canvas

Design System in 90 Days Canvas (FigJam template) is a handy set of useful questions to start a design system effort. Essentially, it’s a roadmap to discuss everything from the value of a design system to stakeholders, teams involved, and components to start with.

A neat little helper to get a design system up and running — and adopted! — in 90 days. Created for small and large companies that are building a design system or plan to set up one. Kindly shared by Dan Mall.

Practical Design System Tactics

Design System Tactics is a practical overview of tactics to help designers make progress with a design system at every stage — from crafting system principles to component discovery to design system office hours to cross-brand consolidation. Wonderful work by the one-and-only Ness Grixti.

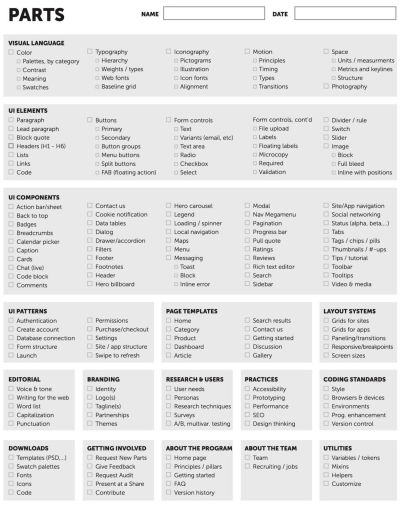

Design System Worksheet (PDF)

Design System Checklist by Nathan Curtis (download the PDF) is a practical 2-page worksheet for a 60-minute team activity, designed to choose the right parts, products, and people for your design system.

Of course, the point of a design system is not to be fully comprehensive or cover every possible component you might ever need. It’s all about being useful enough to help designers produce quality work faster and being flexible enough to help designers make decisions rather than make decisions for them.

Useful Questions To Get Started With

The value of a design system lies in it being useful and applicable — for a large group of people in the organization. And according to Dan, a good start is to identify where exactly that value would be most helpful to tackle the company’s critical challenges and goals:

- What is important to our organization at the highest level?

- Who is important to our design system effort?

- What unofficial systems already exist in design and code?

- Which teams have upcoming needs that a system could solve?

- Which teams have immediate needs that can grow our system?

- Which teams should we and have we talked to?

- Which stakeholders should we and have we talked to?

- What needs, desires, and concerns do our stakeholders have?

- What components do product or feature teams need now or soon?

- What end-user problems/opportunities could a system address?

- What did we learn about using other design systems?

- What is our repeatable process for working on products?

- What components will we start with?

- What needs, desires, and concerns do our stakeholders share?

- Where are our components currently being used or planned for?

Useful Resources

Here are a few other useful little helpers that might help you in your design system efforts:

- Design System Questions To Answer In First 90 Days, by Dan Mall

- Design System Canvas (PDF / Figjam), by Paavan Buddhdev

- LeanDS Framework (Figma), by Marianne Ashton-Booth

- Useful UX Templates For Designers (Figma Kits), by yours truly, Vitaly Friedman

- Design System Guide, by Romina Kavcic

Wrapping Up

A canvas often acts as a great conversation starter. It’s rarely complete, but it brings up topics and issues that one wouldn’t have discovered on the spot. We won’t have answers to all questions right away, but we can start moving in the right direction to turn a design system effort into a success.

Happy crossing off the right tick boxes!

How To Measure UX And Design Impact

Meet Measure UX & Design Impact (8h), a practical guide for designers and UX leads to shape, measure, and explain your incredible UX impact on business. Recorded and updated by Vitaly Friedman. Use the friendly code 🎟 IMPACT to save 20% off today. Jump to the details.

Video + UX Training

$ 495.00 $ 799.00

Get Video + UX Training

25 video lessons (8h) + Live UX Training.

100 days money-back-guarantee.

Video only

$ 250.00$ 395.00

25 video lessons (8h). Updated yearly.

Also available as a UX Bundle with 2 video courses.

Further Reading on Smashing Magazine

- “Build Design Systems With Penpot Components,” Mikołaj Dobrucki

- “How To Turn Your Figma Designs Into Live Apps With Anima Playground,” Anima Team

- “UX And Design Files Organization Template,” Vitaly Friedman

- “The Digital Playbook: A Crucial Counterpart To Your Design System,” Paul Boag

(mrn, yk)

by Admin

Building A Practical UX Strategy Framework

Building A Practical UX Strategy Framework Building A Practical UX Strategy Framework Paul Boag 2025-05-16T11:00:00+00:00 2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00 In my experience, most UX teams find themselves primarily implementing other people’s ideas rather than leading the conversation about user experience. This happens because stakeholders and decision-makers often lack […]

Accessibility

Building A Practical UX Strategy Framework

Paul Boag 2025-05-16T11:00:00+00:00

2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00

In my experience, most UX teams find themselves primarily implementing other people’s ideas rather than leading the conversation about user experience. This happens because stakeholders and decision-makers often lack a deep understanding of UX’s capabilities and potential. Without a clear UX strategy framework, professionals get relegated to a purely tactical role — wireframing and testing solutions conceived by others.

A well-crafted UX strategy framework changes this dynamic. It helps UX teams take control of their role and demonstrate real leadership in improving the user experience. Rather than just responding to requests, you can proactively identify opportunities that deliver genuine business value. A strategic approach also helps educate stakeholders about UX’s full potential while building credibility through measurable results.

Strategy And The Fat Smoker

When I guide teams on creating a UX strategy, I like to keep things simple. I borrow an approach from the book Strategy and the Fat Smoker and break strategy into three clear parts:

- First, we diagnose where we are today.

- Then, we set guiding policies to steer us.

- Finally, we outline actions to get us where we want to go.

Let me walk you through each part so you can shape a UX strategy that feels both practical and powerful.

Diagnosis: Know Your Starting Point

Before we outline any plan, we need to assess our current situation. A clear diagnosis shows where you can make the biggest impact. It also highlights the gaps you must fill.

Identify Status Quo Failures

Start by naming what isn’t working. You might find that your organization lacks a UX team. Or the team has a budget that is too small. Sometimes you uncover that user satisfaction scores are slipping. Frame these challenges in business terms. For example, a slow sign‑up flow may be costing you 20 percent of new registrations each month. That ties UX to revenue and grabs attention.

Once you have a list of failures, ask yourself:

What outcome does each failure hurt?

A slow checkout might reduce e‑commerce sales. Complicated navigation may dent customer retention. Linking UX issues to business metrics makes the case for change.

Map The Aspirational Experience

Next, visualize what an improved journey would look like. A quick way is to create two simple journey maps. One shows the current experience. The other shows an ideal path. Highlight key steps like discovery, sign‑up, onboarding, and support. Then ask:

How will this new journey help meet our business goals?

Maybe faster onboarding can cut support costs. Or a streamlined checkout can boost average order value.

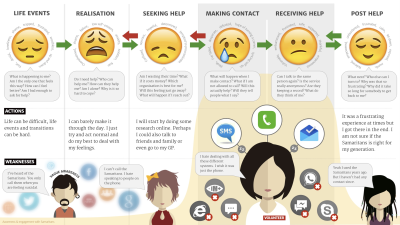

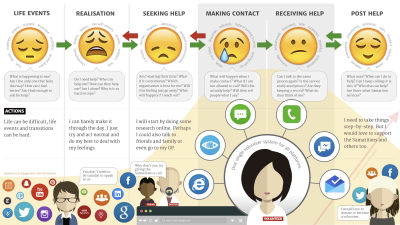

Let me share a real-world example. When working with the Samaritans, a UK mental health charity, we first mapped their current support process. While their telephone support was excellent, they struggled with email and text support, and had no presence on social media platforms. This was largely because volunteers found it difficult to manage multiple communication systems.

We then created an aspirational journey map showing a unified system where volunteers could manage all communication channels through a single interface. This clear vision gave the organization a concrete goal that would improve the experience for both users seeking help and the volunteers providing support.

This vision gives everyone something to rally around. It also guides your later actions by showing the target state.

Audit Resources And Influence

Next, turn your attention to what you have to work with. List your UX team members and their skills. Note any budget set aside for research tools or software licenses. Then identify where you have influence across the organization. Which teams already seek your advice? Who trusts your guidance? That might be the product group or marketing. You’ll lean on these allies to spread UX best practices.

Finally, consider who else matters. Are there policy owners, process leads, or executives you need on board? Jot down names and roles so you can loop them in later.

Spot Your Constraints

Every strategy must live within real‑world limits. Maybe there’s a headcount freeze. Or IT systems won’t support a major overhaul. List any technical, budget, or policy limits you face. Then accept them. You’ll design your strategy to deliver value without asking for impossible changes. Working within constraints boosts your credibility. It also forces creativity.

With the diagnosis complete, we know where we stand. Next, let’s look at how to steer our efforts.

Guiding Policies: Set the North Star

Guiding policies give you guardrails. They help you decide which opportunities to chase and which to skip. These policies reflect your priorities and the best path forward.

Choose A Tactical Or Strategic Approach

Early on, you must pick how your UX team will operate. You have two broad options:

- Tactical

You embed UX people on specific projects. They run tests and design interfaces hands‑on. This needs a bigger team. I like a ratio of one UX pro for every two developers. - Strategic

You act as a center of excellence. You advise other teams. You build guidelines, run workshops, and offer tools. This needs fewer hands but a broader influence.

Weigh your resources against your goals. If you need to move fast on many projects, go tactical. If you want to shift mindsets, work strategically. Choose the approach with the best chance of success.

Define A Prioritization Method

You’ll face many requests for UX work. A clear way to sort them saves headaches. Over the years, I’ve used a simple digital triage. You score each request based on impact, effort, and risk. Then, you work on the highest‑scoring items first. You can adapt this model however you like. The point is to have a repeatable, fair way to say yes or no.

Create A Playbook Of Principles

A playbook holds your core design principles, standard operating procedures, and templates. It might include:

- A design system for UI patterns;

- Standards around accessibility or user research;

- Guides for key tasks such as writing for the web;

- Templates for common activities like user interviews.

This playbook becomes your team’s shared reference. It helps others repeat your process. It also captures the know‑how you need as your team grows.

Plan Your Communication

Strategy fails when people don’t know about it. You need a plan to engage stakeholders. I find it helpful to use a RACI chart — who is Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed. Then decide:

- How often will you send updates?

- Which channels should you use (email, Slack, weekly demos)?

- Who leads each conversation?

Clear, regular communication keeps everyone looped in. It also surfaces concerns early so you can address them.

With guiding policies in place, you have a clear way to decide what to work on. Now, let’s turn to making things happen.

Action Plan: Bring Strategy To Life

Actions are the concrete steps you take to deliver on your guiding policies. They cover the projects you run, the support you give, and the risks you manage.

Outline Key Projects And Services

Start by listing the projects you’ll tackle. These might be:

- Running a discovery phase for a new product.

- Building a design system for your marketing team.

- Conducting user tests on your main flow.

For each project, note what you will deliver and when. You can use your digital triage scores to pick the highest priorities. Keep each project scope small enough to finish in a few sprints. That way, you prove value quickly.

Offer Training And Tools

If you choose a strategic approach, you need to empower others. Plan workshops on core UX topics. Record short videos on testing best practices. Build quick reference guides. Curate a list of tools:

- Prototyping apps,

- Research platforms,

- Analytics dashboards.

Make these resources easy to find in your playbook.

Assign Stakeholder Roles

Your strategy needs executive backing. Identify a senior sponsor who can break through roadblocks. Outline what you need them to do. Maybe it’s championing a new budget line or approving key hires. Also, pin down other collaborators. Who on the product side will help you scope new features? Who on the IT team will support user research tooling? Getting clear roles avoids confusion.

Manage Risks and Barriers

No plan goes off without a hitch. List your biggest risks, such as:

- A hiring freeze delays tactical hires;

- Key stakeholders lose interest;

- Technical debt slows down new releases.

For each risk, jot down how you’ll handle it. Maybe you should shift to a fully strategic approach if hiring stalls. Or you can send a weekly one‑page update to reengage sponsors. Having a fallback keeps you calm when things go sideways.

Before we wrap up, let’s talk about making strategy stick.

Embedding UX Into The Culture

A strategy shines only if you deeply embed it into your organization’s culture. Here’s how to make that happen:

- Build awareness and enthusiasm

- Run regular “lunch and learn” sessions to showcase UX wins.

- Host an annual UX day or mini-conference to boost visibility.

- Create a monthly UX salon where teams share challenges and victories.

- Make UX visible and tangible

- Display personas and journey maps in office spaces.

- Add design principles to everyday items like mousepads and mugs.

- Share success metrics and improvements in company communications.

- Embed UX into processes

- Establish clear UX policies and best practices.

- Review and update procedures that might hinder a good user experience.

- Create a healthy competition between teams through UX metrics.

These tactics transform your strategy from a document into an organizational movement. They foster a culture where everyone thinks about user experience, not just the UX team. Remember, cultural change takes time — but consistent, visible efforts will gradually shift mindsets across the organization.

Implementing Your UX Strategy: From Plan To Practice

We started by diagnosing your current state. Then we set policies to guide your efforts. Finally, we laid out an action plan to deliver results. This three-part framework keeps your UX work tied to real business needs. It also gives you clarity, focus, and credibility.

However, creating a strategy is the easy part — implementing it is where the real challenge lies. This is precisely why the book Strategy and the Fat Smoker carries its distinctive title. Just as someone who is overweight or smokes knows exactly what they need to do, we often know what our UX strategy should be. The difficult part is following through and making it a reality.

Success requires consistent engagement and persistence in the face of setbacks. As Winston Churchill wisely noted,

“Success is going from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.”

This perfectly captures the mindset needed to implement a successful UX strategy — staying committed to your vision even when faced with obstacles and setbacks.

(yk)

by Admin

Fewer Ideas: An Unconventional Approach To Creativity

Fewer Ideas: An Unconventional Approach To Creativity Fewer Ideas: An Unconventional Approach To Creativity Eric Olive 2025-05-15T10:00:00+00:00 2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00 What do the Suez Canal, the Roman Goddess Libertas, and ancient Egyptian sculptures have in common? The Statue of Liberty. Surprising? Sure, but the connections make sense […]

Accessibility

Fewer Ideas: An Unconventional Approach To Creativity

Eric Olive 2025-05-15T10:00:00+00:00

2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00

What do the Suez Canal, the Roman Goddess Libertas, and ancient Egyptian sculptures have in common? The Statue of Liberty.

Surprising? Sure, but the connections make sense when you know the story as recounted by Columbia University psychologist Sheena Iyengar on a recent episode of Hidden Brain.

The French artist Frédéric Bartholdi drew inspiration from Egyptian sculptures when he submitted a design for a sculpture that was going to be built at the Suez Canal.

That plan for the Suez Canal sculpture fell through, leading Bartholdi and a friend to raise money to create a sculpture as a gift to the United States. Bartholdi designed the sculpture after studying the intricacies of the Roman Goddess Libertas, a significant female icon in the late 1800s. He also modeled the statue on Isabelle Boyer, who was 36 years old in 1878. Finally, Bartholdi incorporated his mother’s face into the proposed design. The result? The Statue of Liberty.

Bartholdi’s unorthodox yet methodical approach yielded one of the most famous sculptures in the world.

How did he do it? Did he let his mind run wild? Did he generate endless lists or draw hundreds of plans for each sculpture? Was he a 19th-century brainstorming advocate?

The Problem

“Yes,” would be the answer of many innovation experts today. From stand-ups to workshops and templates to whiteboards, getting the creative juices flowing often involves brainstorming along with the reminder that “there are no bad ideas” and “more ideas are better.” Practiced and repeated so often, this approach to creativity must work, right?

Wrong, says Iyengar. Too many ideas hinder creativity because the human brain can only manage a few ideas at once.

“Creativity requires you to have a bunch of pieces and to not only be able to have them in your memory bank in a way that you can kind of say what they are, but to be able to keep manipulating them in lots of different ways. And that means, you know, in order for your mind to be able to be facile enough to do that, it is going to need fewer pieces.”

— Hidden Brain, “How to be more creative”

Evidence for this view includes a study published by Anne-Laure Sellier of HEC Paris and Darren W. Dahl of British Columbia. The authors compared knitting and crafting in two experimental studies. The results suggested that restricting the number of materials and other creative inputs enhanced the creativity of study participants. The reason was the participants’ ability to enjoy the creative process more, which enhanced their creative output.

A few years ago, I had a similar experience while planning a series of studies. As with any initiative, identifying the scope was key. The problem? Rather than choose from two or three well-defined options, the team discussed several themes at once and then piled on a series of ideas about the best format for presenting these themes: Lists, tables, graphs, images, and flowcharts. The results looked something like this.

A messy whiteboard is not inherently bad. The question is whether brainstorming results like these block or enhance creativity. If the board above seems overwhelming, it’s worth considering a more structured process for creativity and idea generation.

The Solution: Three Ways To Enhance Creativity

Just as Bartholdi approached his designs methodically, designers today can benefit from limits and structure.

In this article, I’ll shed light on three techniques that enhance creativity:

Tip 1: Controlled Curiosity

In today’s world, it’s easy to fall into the trap of believing that creativity comes from simply exposing yourself to a flood of information — scrolling endlessly, consuming random facts, and filling your mind with disconnected data points. It’s a trap because mindless absorption of information without understanding the purpose or deeper context won’t make you more creative.

True creativity is fueled by curiosity, the drive to know more. Curiosity is powerful because it acts as an internal compass, guiding our search for knowledge with intention.

When you’re curious, you don’t just passively take in information; you actively seek it with a purpose.

You have a question in mind, a direction, a reason that shapes the way you explore. This sense of purpose transforms information from a chaotic influx of data into structured, meaningful insights that the brain can organize, categorize, and retrieve when needed.

In my role as a user experience (UX) researcher, I recently needed to review 100+ internal and industry research papers to establish and understand what was already known about a specific subject. The challenge was how to sort, organize, and absorb this information without feeling overwhelmed. Was it better to leverage AI tools like Gemini or ChatGPT to summarize this body of knowledge? How reliable would these summaries be? Was it better to read the executive summaries and copy a few themes to include in a synopsis of all of these papers? What was the best way to organize this information? Which tool should I use to summarize and organize?

Faced with a tight deadline and mounting stress, I paused to reassess. To avoid spiraling, I asked: What are the core objectives of this research review? I then defined three key goals:

- Extract three to five themes to present to several internal teams.

- Craft a research plan pegged to these themes.

- Leverage these themes to inform a series of screens that the design team would create to test with real users.

With clearly defined objectives, I had a purpose. This purpose allowed me to channel my innate curiosity because I knew why I was wading through so much material and who would read and review the synthesis. Curiosity drove me to explore this large body of research, but purpose kept me focused.

Curiosity is the drive to learn more. Creativity requires curiosity because, without this drive, designers and researchers are less likely to explore new ideas or new approaches to problem-solving. The good news is that research and design attract the naturally curious.

The key lies in transforming curiosity into focused exploration. It’s less about the volume of information absorbed and more about the intent behind the inquiry, the depth of engagement, and the strategic application of acquired knowledge.

“

Purposeful curiosity is the difference between drowning in a sea of knowledge and navigating it with mastery.

Tip 2: Imposing Constraints And Making A Plan

Just as purpose makes it easier to focus, constraint also contributes to creativity. Brainstorming 50 ideas might seem creative but can actually prove more distracting than energizing. Limiting the number of ideas is more productive.

“Some people think that having constraints means they can’t be creative. The research shows that people are more creative when there are constraints.”

— Dr. Susan Weinschenk, “The Role of Creativity in Design”

The point is not to limit creativity and innovation but to nurture it with structure. Establishing constraints enhances creativity by focusing idea generation around a few key themes.

Here are two ways to focus on idea generation:

- During meetings and workshops, how might we (HMW) statements help concentrate discussion while still leaving room for a variety of ideas? For example, “How might we condense this 15-step workflow without omitting essential information?”

- Identify the problem and conduct two exercises to test solutions. For example, three customer surveys conducted over the past six months show a consistent pattern: 30% of customers are dissatisfied with their call center experience, and time-on-call has increased over the same six-month period. Divide the team into two groups.

- Group 1 writes two new versions of the greeting customer service representatives (CSRs) use when a customer calls. The next step is an A/B test.

- Group 2 identifies two steps to remove from the current CSR script. The next step is a trial run with CSRs to record time-on-call and customer satisfaction with the call.

“Constraint” can be negative, such as a restriction or limitation, but it can also refer to exhibiting control and restraint.

By exercising restraint, you and your team can cultivate higher-quality ideas and concentrate on solutions. Rather than generate 50 ideas about how to reconfigure an entire call center setup, it is more productive to focus on two metrics: time-on-task and the customer’s self-rated satisfaction when contacting the call center.

By channeling this concentrated energy towards well-defined challenges, your team can then effectively pursue innovative solutions for two closely related issues.

Tip 3: Look To Other Domains

Other domains or subject areas can be a valuable source of innovative solutions. When facing a challenging design problem, limiting ideas but reaching beyond the immediate domain is a powerful combination.

The high-stakes domain of airplane design provides a useful case study of how to simultaneously limit ideas and look to other domains to solve a design problem. Did you know that Otto Lilienthal, a 19th-century design engineer, was the first person to make repeated, successful flights with gliders?

Maybe not, but you’ve likely heard of the Wright brothers, whose work launched modern aviation. Why? Lilienthal’s work, while essential, relied on a design based on a bird’s wings, requiring the person flying the glider to move their entire body to change direction. This design ultimately proved fatal when Lilienthal was unable to steer out of a nosedive and crashed.

The Wright brothers were bike mechanics who leveraged their knowledge of balance to create a steering mechanism for pilots. By looking outside the “flight domain,” the Wright brothers found a way to balance and steer planes and ultimately transformed aviation.

In a similar fashion, Bartholdi, the French artist who sculpted the Statue of Liberty, did not limit himself to looking at statues in Paris. He traveled to Egypt, studied coins and paintings, and drew inspiration from his mother’s face.

Designers seeking inspiration should step away from the screen to paint, write a poem, or build a sculpture with popsicle sticks. In other words, paint with oils, not pixels; write with ink, not a keyboard; sculpt with sticks, not white space.

On its face, seeking inspiration from other disciplines would seem to contradict Tip 2 above — impose constraints. Examined from another angle, however, imposing constraints and exploring domains are complementary techniques.

Rather than list ten random ideas on a whiteboard, it’s more productive to focus on a few solutions and think about these solutions from a variety of angles. For example, recently, I found myself facing a high volume of ideas, source material, and flow charts. While organizing this information was manageable, distilling it into a form others could absorb proved challenging.

Rather than generate a list of ten ways to condense this information, I took the dog for a walk and let my eyes wander while strolling through the park. What did I see when my eyes lit upon barren trees? Branches. And what do flow charts do? They branch into different directions.

Upon finishing the walk, I jumped back online and began organizing my source material into a series of branched flows. Was this wildly innovative? No. Was this the first time I had drawn flowcharts with branches? Also no. The difference in this case was the application of the branching solution for all of my source material, not only the flow charts. In short, a walk and a nudge from nature’s design helped me escape the constraints imposed by a two-dimensional screen.

Stepping away from the screen is, of course, good for our mental and physical health. The occasional light bulb moment is a bonus and one I’m happy to accept.

Conclusion

Yet these moments alone are not enough. You must channel inspiration by applying practical techniques to move forward with design and analysis lest you become overwhelmed by so many ideas that you become paralyzed and unable to make a decision.

To avoid paralysis and reduce the chances of wasting time, I’ve argued against brainstorming, endless lists, and wall-to-wall post-its. Instead, I’ve proposed three practical techniques to boost creativity.

Controlled curiosity.

From brainstorming to endless scrolling, exposing yourself to high volumes of information is a trap because absorbing information without understanding the purpose or deeper context won’t make you more creative.

The solution lies in transforming curiosity into focused exploration. Purposeful curiosity allows you to explore, think, and identify solutions without drowning in a sea of information.

Imposing constraints.

Brainstorming long lists of ideas might seem creative, but can actually prove more distracting than energizing.

The solution is to nurture creativity with structure by limiting the number of ideas under consideration.

This structure enhances creativity by focusing idea generation around a few key themes.

Look beyond your immediate domain.

Otto Lilienthal’s fatal glider crash shows what can happen when solutions are examined through the single lens of one subject area.

The solution is to concentrate on innovative solutions for a single issue while reflecting on the problem from various perspectives, such as two-dimensional design, three-dimensional design, or design in nature.

Resources

- How to be More Creative, Hidden Brain Media

- “Focus Creative Success is Enjoyed through Restricted Choice” by Annie Laure-Sellier and Darren W. Dahl

Further Reading on Smashing Magazine

- “Boosting Up Your Creativity Without Endless Reference Scrolling,” Marina Chernyshova

- “UX And Design Files Organization Template,” Vitaly Friedman

- “The Scent Of UX: The Unrealized Potential Of Olfactory Design,” Kristian Mikhel

- “Fostering An Accessibility Culture,” Daniel Devesa Derksen-Staats

(yk)

by Admin

How To Launch Big Complex Projects

How To Launch Big Complex Projects How To Launch Big Complex Projects Vitaly Friedman 2025-05-05T10:00:00+00:00 2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00 Think about your past projects. Did they finish on time and on budget? Did they end up getting delivered without cutting corners? Did they get disrupted along the way […]

Accessibility

How To Launch Big Complex Projects

Vitaly Friedman 2025-05-05T10:00:00+00:00

2025-06-25T15:04:30+00:00

Think about your past projects. Did they finish on time and on budget? Did they end up getting delivered without cutting corners? Did they get disrupted along the way with a changed scope, conflicted interests, unexpected delays, and surprising blockers?

Chances are high that your recent project was over schedule and over budget — just like a vast majority of other complex UX projects. Especially if it entailed at least some sort of complexity, be it a large group of stakeholders, a specialized domain, internal software, or expert users. It might have been delayed, moved, canceled, “refined,” or postponed. As it turns out, in many teams, shipping on time is an exception rather than the rule.

In fact, things almost never go according to plan — and on complex projects, they don’t even come close. So, how can we prevent it from happening? Well, let’s find out.

99.5% Of Big Projects Overrun Budgets And Schedules

As people, we are inherently over-optimistic and over-confident. It’s hard to study and process everything that can go wrong, so we tend to focus on the bright side. However, unchecked optimism leads to unrealistic forecasts, poorly defined goals, better options ignored, problems not spotted, and no contingencies to counteract the inevitable surprises.

Hofstadter’s Law states that the time needed to complete a project will always expand to fill the available time &- even if you take into account Hofstadter’s Law. Put differently, it always takes longer than you expect, however cautious you might be.

As a result, only 0.5% of big projects make the budget and the schedule — e.g., big relaunches, legacy re-dos, big initiatives. We might try to mitigate risk by adding 15–20% buffer — but it rarely helps. Many of these projects don’t follow “normal” (Bell curve) distribution, but are rather “fat-tailed”.

And there, overruns of 60–500% are typical and turn big projects into big disasters.

Reference-Class Forecasting (RCF)

We often assume that if we just thoroughly collect all the costs needed and estimate complexity or efforts, we should get a decent estimate of where we will eventually land. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Complex projects have plenty of unknown unknowns. No matter how many risks, dependencies, and upstream challenges we identify, there are many more we can’t even imagine. The best way to be more accurate is to define a realistic anchor — for time, costs, and benefits — from similar projects done in the past.

Reference-class forecasting follows a very simple process:

- First, we find the reference projects that have the most similarities to our project.

- If the distribution follows the Bell curve, use the mean value + 10–15% contingency.

- If the distribution is fat-tailed, invest in profound risk management to prevent big challenges down the line.

- Tweak the mean value only if you have very good reasons to do so.

- Set up a database to track past projects in your company (for cost, time, benefits).

Mapping Out Users’ Success Moments

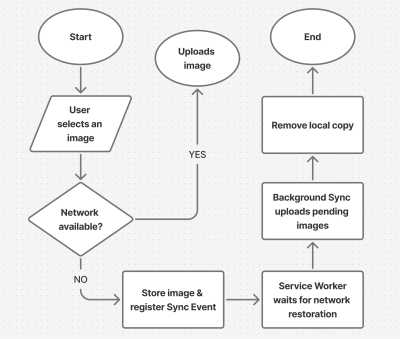

Over the last few years, I’ve been using the technique called “Event Storming,” suggested by Matteo Cavucci many years back. The idea is to capture users’ experience moments through the lens of business needs. With it, we focus on the desired business outcome and then use research insights to project events that users will be going through to achieve that outcome.

The image above shows the process in action — with different lanes representing different points of interest, and prioritized user events themed into groups, along with risks, bottlenecks, stakeholders, and users to be involved — as well as UX metrics. From there, we can identify common themes that emerge and create a shared understanding of risks, constraints, and people to be involved.

Throughout that journey, we identify key milestones and break users’ events into two main buckets:

- User’s success moments (which we want to dial up ↑);

- User’s pain points or frustrations (which we want to dial down ↓).

We then break out into groups of 3–4 people to separately prioritize these events and estimate their impact and effort on Effort vs. Value curves by John Cutler.

The next step is identifying key stakeholders to engage with, risks to consider (e.g., legacy systems, 3rd-party dependency, etc.), resources, and tooling. We reserve special time to identify key blockers and constraints that endanger a successful outcome or slow us down. If possible, we also set up UX metrics to track how successful we actually are in improving the current state of UX.

It might seem like a bit too much planning for just a UX project, but it has been helping quite significantly to reduce failures and delays and also maximize business impact.

When speaking to businesses, I usually speak about better discovery and scoping as the best way to mitigate risk. We can, of course, throw ideas into the market and run endless experiments. But not for critical projects that get a lot of visibility, e.g., replacing legacy systems or launching a new product. They require thorough planning to prevent big disasters, urgent rollbacks, and… black swans.

Black Swan Management

Every other project encounters what’s called a Black Swan — a low probability, high-consequence event that is more likely to occur when projects stretch over longer periods of time. It could be anything from restructuring teams to a change of priorities, which then leads to cancellations and rescheduling.

Little problems have an incredible capacity to compound large, disastrous problems — ruining big projects and sinking big ambitions at a phenomenal scale. The more little problems we can design around early, the more chances we have to get the project out the door successfully.

So we make projects smaller and shorter. We mitigate risks by involving stakeholders early. We provide less surface for Black Swans to emerge. One good way to get there is to always start every project with a simple question: “Why are we actually doing this project?” The answers often reveal not just motivations and ambitions, but also the challenges and dependencies hidden between the lines of the brief.

And as we plan, we could follow a “right-to-left thinking”. We don’t start with where we are, but rather where we want to be. And as we plan and design, we move from the future state towards the current state, studying what’s missing or what’s blocking us from getting there. The trick is: we always keep our end goal in mind, and our decisions and milestones are always shaped by that goal.

Manage Deficit Of Experience

Complex projects start with a deep deficit of experience. To increase the chances of success, we need to minimize the chance of mistakes even happening. That means trying to make the process as repetitive as possible — with smaller “work modules” repeated by teams over and over again.

🚫 Beware of unchecked optimism → unrealistic forecasts.

🚫 Beware of “cutting-edge” → untested technology spirals risk.

🚫 Beware of “unique” → high chance of exploding costs.

🚫 Beware of “brand new” → rely on tested and reliable.

🚫 Beware of “the biggest” → build small things, then compose.

It also means relying on reliable: from well-tested tools to stable teams that have worked well together in the past. Complex projects aren’t a good place to innovate processes, mix-n-match teams, and try out more affordable vendors.

Typically, these are extreme costs in disguise, skyrocketing delivery delays, and unexpected expenses.

Think Slow, Act Fast

In the spirit of looming deadlines, many projects rush into delivery mode before the scope of the project is well-defined. It might work for fast experiments and minor changes, but that’s a red flag for larger projects. The best strategy is to spend more time in planning before designing a single pixel on the screen.

But planning isn’t an exercise in abstract imaginative work. Good planning should include experiments, tests, simulations, and refinements. It must include the steps of how we reduce risks and how we mitigate risks when something unexpected (but frequent in other similar projects) happens.

Good Design Is Good Risk Management

When speaking about design and research to senior management, position it as a powerful risk management tool. Good design that involves concept testing, experimentation, user feedback, iterations, and refinement of the plan is cheap and safe.