by Admin

A Week In The Life Of An AI-Augmented Designer

A Week In The Life Of An AI-Augmented Designer A Week In The Life Of An AI-Augmented Designer Lyndon Cerejo 2025-08-22T08:00:00+00:00 2025-08-27T15:32:36+00:00 Artificial Intelligence isn’t new, but in November 2022, something changed. The launch of ChatGPT brought AI out of the background and into everyday […]

Accessibility

by Admin

The Double-Edged Sustainability Sword Of AI In Web Design

The Double-Edged Sustainability Sword Of AI In Web Design The Double-Edged Sustainability Sword Of AI In Web Design Alex Williams 2025-08-20T10:00:00+00:00 2025-08-21T11:03:55+00:00 Artificial intelligence is increasingly automating large parts of design and development workflows — tasks once reserved for skilled designers and developers. This streamlining […]

Accessibility

by Admin

Beyond The Hype: What AI Can Really Do For Product Design

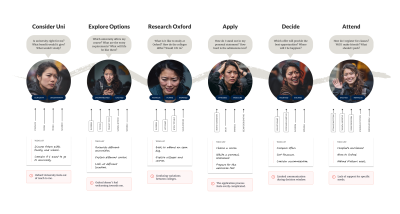

Beyond The Hype: What AI Can Really Do For Product Design Beyond The Hype: What AI Can Really Do For Product Design Nikita Samutin 2025-08-18T13:00:00+00:00 2025-08-21T11:03:55+00:00 These days, it’s easy to find curated lists of AI tools for designers, galleries of generated illustrations, and countless […]

Accessibility

Handling JavaScript Event Listeners With Parameters

by Admin

Handling JavaScript Event Listeners With Parameters Handling JavaScript Event Listeners With Parameters Amejimaobari Ollornwi 2025-07-21T10:00:00+00:00 2025-07-23T15:03:27+00:00 JavaScript event listeners are very important, as they exist in almost every web application that requires interactivity. As common as they are, it is also essential for them to […]

Accessibility

Handling JavaScript Event Listeners With Parameters

Amejimaobari Ollornwi 2025-07-21T10:00:00+00:00

2025-07-23T15:03:27+00:00

JavaScript event listeners are very important, as they exist in almost every web application that requires interactivity. As common as they are, it is also essential for them to be managed properly. Improperly managed event listeners can lead to memory leaks and can sometimes cause performance issues in extreme cases.

Here’s the real problem: JavaScript event listeners are often not removed after they are added. And when they are added, they do not require parameters most of the time — except in rare cases, which makes them a little trickier to handle.

A common scenario where you may need to use parameters with event handlers is when you have a dynamic list of tasks, where each task in the list has a “Delete” button attached to an event handler that uses the task’s ID as a parameter to remove the task. In a situation like this, it is a good idea to remove the event listener once the task has been completed to ensure that the deleted element can be successfully cleaned up, a process known as garbage collection.

A Common Mistake When Adding Event Listeners

A very common mistake when adding parameters to event handlers is calling the function with its parameters inside the addEventListener() method. This is what I mean:

button.addEventListener('click', myFunction(param1, param2));

The browser responds to this line by immediately calling the function, irrespective of whether or not the click event has happened. In other words, the function is invoked right away instead of being deferred, so it never fires when the click event actually occurs.

You may also receive the following console error in some cases:

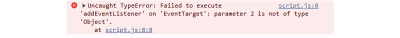

addEventListener on EventTarget: parameter is not of type Object. (Large preview)

This error makes sense because the second parameter of the addEventListener method can only accept a JavaScript function, an object with a handleEvent() method, or simply null. A quick and easy way to avoid this error is by changing the second parameter of the addEventListener method to an arrow or anonymous function.

button.addEventListener('click', (event) => {

myFunction(event, param1, param2); // Runs on click

});

The only hiccup with using arrow and anonymous functions is that they cannot be removed with the traditional removeEventListener() method; you will have to make use of AbortController, which may be overkill for simple cases. AbortController shines when you have multiple event listeners to remove at once.

For simple cases where you have just one or two event listeners to remove, the removeEventListener() method still proves useful. However, in order to make use of it, you’ll need to store your function as a reference to the listener.

Using Parameters With Event Handlers

There are several ways to include parameters with event handlers. However, for the purpose of this demonstration, we are going to constrain our focus to the following two:

Option 1: Arrow And Anonymous Functions

Using arrow and anonymous functions is the fastest and easiest way to get the job done.

To add an event handler with parameters using arrow and anonymous functions, we’ll first need to call the function we’re going to create inside the arrow function attached to the event listener:

const button = document.querySelector("#myButton");

button.addEventListener("click", (event) => {

handleClick(event, "hello", "world");

});

After that, we can create the function with parameters:

function handleClick(event, param1, param2) {

console.log(param1, param2, event.type, event.target);

}

Note that with this method, removing the event listener requires the AbortController. To remove the event listener, we create a new AbortController object and then retrieve the AbortSignal object from it:

const controller = new AbortController();

const { signal } = controller;

Next, we can pass the signal from the controller as an option in the removeEventListener() method:

button.addEventListener("click", (event) => {

handleClick(event, "hello", "world");

}, { signal });

Now we can remove the event listener by calling AbortController.abort():

controller.abort()

Option 2: Closures

Closures in JavaScript are another feature that can help us with event handlers. Remember the mistake that produced a type error? That mistake can also be corrected with closures. Specifically, with closures, a function can access variables from its outer scope.

In other words, we can access the parameters we need in the event handler from the outer function:

function createHandler(message, number) {

// Event handler

return function (event) {

console.log(`${message} ${number} - Clicked element:`, event.target);

};

}

const button = document.querySelector("#myButton");

button.addEventListener("click", createHandler("Hello, world!", 1));

}

This establishes a function that returns another function. The function that is created is then called as the second parameter in the addEventListener() method so that the inner function is returned as the event handler. And with the power of closures, the parameters from the outer function will be made available for use in the inner function.

Notice how the event object is made available to the inner function. This is because the inner function is what is being attached as the event handler. The event object is passed to the function automatically because it’s the event handler.

To remove the event listener, we can use the AbortController like we did before. However, this time, let’s see how we can do that using the removeEventListener() method instead.

In order for the removeEventListener method to work, a reference to the createHandler function needs to be stored and used in the addEventListener method:

function createHandler(message, number) {

return function (event) {

console.log(`${message} ${number} - Clicked element:`, event.target);

};

}

const handler = createHandler("Hello, world!", 1);

button.addEventListener("click", handler);

Now, the event listener can be removed like this:

button.removeEventListener("click", handler);

Conclusion

It is good practice to always remove event listeners whenever they are no longer needed to prevent memory leaks. Most times, event handlers do not require parameters; however, in rare cases, they do. Using JavaScript features like closures, AbortController, and removeEventListener, handling parameters with event handlers is both possible and well-supported.

(gg, yk)

by Admin

Why Non-Native Content Designers Improve Global UX

Why Non-Native Content Designers Improve Global UX Why Non-Native Content Designers Improve Global UX Oleksii Tkachenko 2025-07-18T13:00:00+00:00 2025-07-23T15:03:27+00:00 A few years ago, I was in a design review at a fintech company, polishing the expense management flows. It was a routine session where we reviewed […]

Accessibility

Why Non-Native Content Designers Improve Global UX

Oleksii Tkachenko 2025-07-18T13:00:00+00:00

2025-07-23T15:03:27+00:00

A few years ago, I was in a design review at a fintech company, polishing the expense management flows. It was a routine session where we reviewed the logic behind content and design decisions.

While looking over the statuses for submitted expenses, I noticed a label saying ‘In approval’. I paused, re-read it again, and asked myself:

“Where is it? Are the results in? Where can I find them? Are they sending me to the app section called “Approval”?”

This tiny label made me question what was happening with my money, and this feeling of uncertainty was quite anxiety-inducing.

My team, all native English speakers, did not flinch, even for a second, and moved forward to discuss other parts of the flow. I was the only non-native speaker in the room, and while the label made perfect sense to them, it still felt off to me.

After a quick discussion, we landed on ‘Pending approval’ — the simplest and widely recognised option internationally. More importantly, this wording makes it clear that there’s an approval process, and it hasn’t taken place yet. There’s no need to go anywhere to do it.

Some might call it nitpicking, but that was exactly the moment I realised how invisible — yet powerful — the non-native speaker’s perspective can be.

In a reality where user testing budgets aren’t unlimited, designing with familiar language patterns from the start helps you prevent costly confusions in the user journey.

“

Those same confusions often lead to:

- Higher rate of customer service queries,

- Lower adoption rates,

- Higher churn,

- Distrust and confusion.

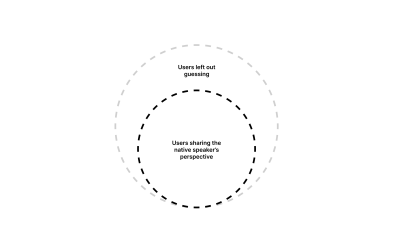

As A Native Speaker, You Don’t See The Whole Picture

Global products are often designed with English as their primary language. This seems logical, but here’s the catch:

Roughly 75% of English-speaking users are not native speakers, which means 3 out of every 4 users.

Native speakers often write on instinct, which works much like autopilot. This can often lead to overconfidence in content that, in reality, is too culturally specific, vague, or complex. And that content may not be understood by 3 in 4 people who read it.

If your team shares the same native language, content clarity remains assumed by default rather than proven through pressure testing.

The price for that is the accessibility of your product. A study by National Library of Medicine found that US adults who had proficiency in English but did not use it as their primary language were significantly less likely to be insured, even when provided with the same level of service as everyone else.

In other words, they did not finish the process of securing a healthcare provider — a process that’s vital to their well-being, in part, due to unclear or inaccessible communication.

If people abandon the process of getting something as vital as healthcare insurance, it’s easy to imagine them dropping out during checkout, account setup, or app onboarding.

Non-native content designers, by contrast, do not write on autopilot. Because of their experience learning English, they’re much more likely to tune into nuances, complexity, and cultural exclusions that natives often overlook. That’s the key to designing for everyone rather than 1 in 4.

Non-native Content Designers Make Your UX Global

Spotting The Clutter And Cognitive Load Issues

When a non-native speaker has to pause, re-read something, or question the meaning of what’s written, they quickly identify it as a friction point in the user experience.

Why it’s important: Every extra second users have to spend understanding your content makes them more likely to abandon the task. This is a high price that companies pay for not prioritising clarity.

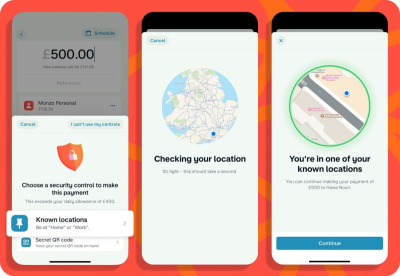

Cognitive load is not just about complex sentences but also about the speed. There’s plenty of research confirming that non-native speakers read more slowly than native speakers. This is especially important when you work on the visibility of system status — time-sensitive content that the user needs to scan and understand quickly.

One example you can experience firsthand is an ATM displaying a number of updates and instructions. Even when they’re quite similar, it still overwhelms you when you realise that you missed one, not being able to finish reading.

This kind of rapid-fire updates can increase frustration and the chances of errors.

Always Advocating For Plain English

They tend to review and rewrite things more often to find the easiest way to communicate the message. What a native speaker may consider clear enough might be dense or difficult for a non-native to understand.

Why it’s important: Simple content better scales across countries, languages, and cultures.

Catching Culture-specific Assumptions And References

When things do not make sense, non-native speakers challenge them. Besides the idioms and other obvious traps, native speakers tend to fall into considering their life experience to be shared with most English-speaking users.

Cultural differences might even exist within one globally shared language. Have you tried saying ‘soccer’ instead of ‘football’ in a conversation with someone from the UK? These details may not only cause confusion but also upset people.

Why it’s important: Making sure your product is free from culture-specific references makes your product more inclusive and safeguards you from alienating your users.

They Have Another Level Of Empathy For The Global Audience

Being a non-native speaker themselves, they have experience with products that do not speak clearly to them. They’ve been in the global user’s shoes and know how it impacts the experience.

Why it’s important: Empathy is a key driver towards design decisions that take into account the diverse cultural and linguistic background of the users.

How Non-native Content Design Can Shape Your Approach To Design

Your product won’t become better overnight simply because you read an inspiring article telling you that you need to have a more diverse team. I get it. So here are concrete changes that you can make in your design workflows and hiring routines to make sure your content is accessible globally.

Run Copy Reviews With Non-native Readers

When you launch a new feature or product, it’s a standard practice to run QA sessions to review visuals and interactions. When your team does not include the non-native perspective, the content is usually overlooked and considered fine as long as it’s grammatically correct.

I know, having a dedicated localisation team to pressure-test your content for clarity is a privilege, but you can always start small.

At one of my previous companies, we established a ‘clarity heroes council’ — a small team of non-native English speakers with diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. During our reviews, they often asked questions that surprised us and highlighted where clarity was missing:

- What’s a “grace period”?

- What will happen when I tap “settle the payment”?

These questions flag potential problems and help you save both money and reputation by avoiding thousands of customer service tickets.

Review Existing Flows For Clarity

Even if your product does not have major releases regularly, it accumulates small changes over time. They’re often plugged in as fixes or small improvements, and can be easily overlooked from a QA perspective.

A good start will be a regular look at the flows that are critical to your business metrics: onboarding, checkout, and so on. Fence off some time for your team quarterly or even annually, depending on your product size, to come together and check whether your key content pieces serve the global audience well.

Usually, a proper review is conducted by a team: a product designer, a content designer, an engineer, a product manager, and a researcher. The idea is to go over the flows, research insights, and customer feedback together. For that, having a non-native speaker on the audit task force will be essential.

If you’ve never done an audit before, try this template as it covers everything you need to start.

Make Sure Your Content Guidelines Are Global-ready

If you haven’t done it already, make sure your voice & tone documentation includes details about the level of English your company is catering to.

This might mean working with the brand team to find ways to make sure your brand voice comes through to all users without sacrificing clarity and comprehension. Use examples and showcase the difference between sounding smart or playful vs sounding clear.

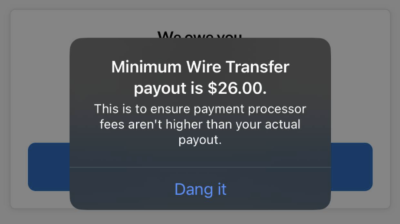

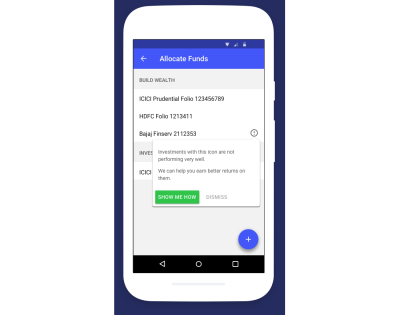

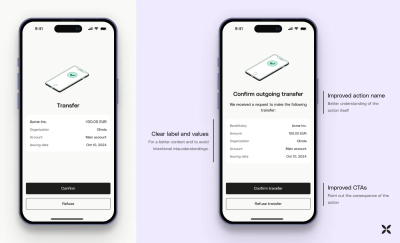

Leaning too much towards brand personality is where cultural differences usually shine through. As a user, you might’ve seen it many times. Here’s a banking app that wanted to seem relaxed and relatable by introducing ‘Dang it’ as the only call-to-action on the screen.

However, users with different linguistic backgrounds might not be familiar with this expression. Worse, they might see it as an action, leaving them unsure of what will actually happen after tapping it.

Considering how much content is generated with AI today, your guidelines have to account for both tone and clarity. This way, when you feed these requirements to the AI, you’ll see the output that will not just be grammatically correct but also easy to understand.

Incorporate Global English Heuristics Into Your Definition Of Success

Basic heuristic principles are often documented as a part of overarching guidelines to help UX teams do a better job. The Nielsen Norman Group usability heuristics cover the essential ones, but it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t introduce your own. To complement this list, add this principle:

Aim for global understanding: Content and design should communicate clearly to any user regardless of cultural or language background.

You can suggest criteria to ensure it’s clear how to evaluate this:

- Action transparency: Is it clear what happens next when the user proceeds to the next screen or page?

- Minimal ambiguity: Is the content open to multiple interpretations?

- International clarity: Does this content work in a non-Western context?

Bring A Non-native Perspective To Your Research, Too

This one is often overlooked, but collaboration between the research team and non-native speaking writers is super helpful. If your research involves a survey or interview, they can help you double-check whether there is complex or ambiguous language used in the questions unintentionally.

In a study by the Journal of Usability Studies, 37% of non-native speakers did not manage to answer the question that included a word they did not recognise or could not recall the meaning of. The question was whether they found the system to be “cumbersome to use”, and the consequences of getting unreliable data and measurements on this would have a negative impact on the UX of your product.

Another study by UX Journal of User Experience highlights how important clarity is in surveys. While most people in their study interpreted the question “How do you feel about … ?” as “What’s your opinion on …?”, some took it literally and proceeded to describe their emotions instead.

This means that even familiar terms can be misinterpreted. To get precise research results, it’s worth defining key terms and concepts to ensure common understanding with participants.

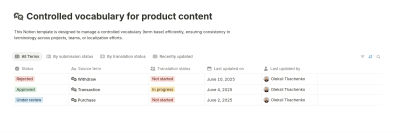

Globalise Your Glossary

At Klarna, we often ran into a challenge of inconsistent translation for key terms. A well-defined English term could end up having from three to five different versions in Italian or German. Sometimes, even the same features or app sections could be referred to differently depending on the market — this led to user confusion.

To address this, we introduced a shared term base — a controlled vocabulary that included:

- English term,

- Definition,

- Approved translations for all markets,

- Approved and forbidden synonyms.

Importantly, the term selection was dictated by user research, not by assumption or personal preferences of the team.

If you’re unsure where to begin, use this product content vocabulary template for Notion. Duplicate it for free and start adding your terms.

We used a similar setup. Our new glossary was shared internally across teams, from product to customer service. Results? Reducing the support tickets related to unclear language used in UI (or directions in the user journey) by 18%. This included tasks like finding instructions on how to make a payment (especially with the least popular payment methods like bank transfer), where the late fee details are located, or whether it’s possible to postpone the payment. And yes, all of these features were available, and the team believed they were quite easy to find.

A glossary like this can live as an add-on to your guidelines. This way, you will be able to quickly get up to speed new joiners, keep product copy ready for localisation, and defend your decisions with stakeholders.

Approach Your Team Growth With An Open Mind

‘Looking for a native speaker’ still remains a part of the job listing for UX Writers and content designers. There’s no point in assuming it’s intentional discrimination. It’s just a misunderstanding that stems from not fully accepting that our job is more about building the user experience than writing texts that are grammatically correct.

Here are a few tips to make sure you hire the best talent and treat your applicants fairly:

- Remove the ‘native speaker’ and ‘fluency’ requirement.

Instead, focus on the core part of our job: add ‘clear communicator’, ‘ability to simplify’, or ‘experience writing for a global audience’.

- Judge the work, not the accent.

Over the years, there have been plenty of studies confirming that the accent bias is real — people having an unusual or foreign accent are considered less hirable. While some may argue that it can have an impact on the efficiency of internal communications, it’s not enough to justify the reason to overlook the good work of the applicant.

My personal experience with the accent is that it mostly depends on the situation you’re in. When I’m in a friendly environment and do not feel anxiety, my English flows much better as I do not overthink how I sound. Ironically, sometimes when I’m in a room with my team full of British native speakers, I sometimes default to my Slavic accent. The question is: does it make my content design expertise or writing any worse? Not in the slightest.

Therefore, make sure you judge the portfolios, the ideas behind the interview answers, and whiteboard challenge presentations, instead of focusing on whether the candidate’s accent implies that they might not be good writers.

Good Global Products Need Great Non-native Content Design

Non-native content designers do not have a negative impact on your team’s writing. They sharpen it by helping you look at your content through the lens of your real user base. In the globalised world, linguistic purity no longer benefits your product’s user experience.

Try these practical steps and leverage the non-native speaking lens of your content designers to design better international products.

(yk)

by Admin

Unmasking The Magic: The Wizard Of Oz Method For UX Research

Unmasking The Magic: The Wizard Of Oz Method For UX Research Unmasking The Magic: The Wizard Of Oz Method For UX Research Victor Yocco 2025-07-10T10:00:00+00:00 2025-07-16T16:32:47+00:00 New technologies and innovative concepts frequently enter the product development lifecycle, promising to revolutionize user experiences. However, even the […]

Accessibility

Unmasking The Magic: The Wizard Of Oz Method For UX Research

Victor Yocco 2025-07-10T10:00:00+00:00

2025-07-16T16:32:47+00:00

New technologies and innovative concepts frequently enter the product development lifecycle, promising to revolutionize user experiences. However, even the most ingenious ideas risk failure without a fundamental grasp of user interaction with these new experiences.

Consider the plight of the Nintendo Power Glove. Despite being a commercial success (selling over 1 million units), its release in late 1989 was followed by its discontinuation less than a full year later in 1990. The two games created solely for the Power Glove sold poorly, and there was little use for the Glove with Nintendo’s already popular traditional console games.

A large part of the failure was due to audience reaction once the product (which allegedly was developed in 8 weeks) was cumbersome and unintuitive. Users found syncing the glove to the moves in specific games to be extremely frustrating, as it required a process of coding the moves into the glove’s preset move buttons and then remembering which buttons would generate which move. With the more modern success of Nintendo’s WII and other movement-based controller consoles and games, we can see the Power Glove was a concept ahead of its time.

If Power Glove’s developers wanted to conduct effective research prior to building it out, they would have needed to look beyond traditional methods, such as surveys and interviews, to understand how a user might truly interact with the Glove. How could this have been done without a functional prototype and slowing down the overall development process?

Enter the Wizard of Oz method, a potent tool for bridging the chasm between abstract concepts and tangible user understanding, as one potential option. This technique simulates a fully functional system, yet a human operator (“the Wizard”) discreetly orchestrates the experience. This allows researchers to gather authentic user reactions and insights without the prerequisite of a fully built product.

The Wizard of Oz (WOZ) method is named in tribute to the similarly named book by Frank L. Baum. In the book, the Wizard is simply a man hidden behind a curtain, manipulating the reality of those who travel the land of Oz. Dorothy, the protagonist, exposes the Wizard for what he is, essentially an illusion or a con who is deceiving those who believe him to be omnipotent. Similarly, WOZ takes technologies that may or may not currently exist and emulates them in a way that should convince a research participant they are using an existing system or tool.

WOZ enables the exploration of user needs, validation of nascent concepts, and mitigation of development risks, particularly with complex or emerging technologies.

The product team in our above example might have used this method to have users simulate the actions of wearing the glove, programming moves into the glove, and playing games without needing a fully functional system. This could have uncovered the illogical situation of asking laypeople to code their hardware to be responsive to a game, show the frustration one encounters when needing to recode the device when changing out games, and also the cumbersome layout of the controls on the physical device (even if they’d used a cardboard glove with simulated controls drawn in crayon on the appropriate locations.

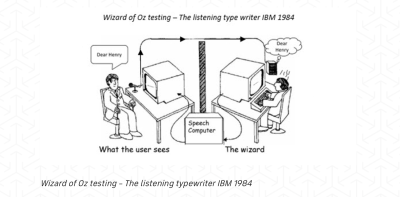

Jeff Kelley credits himself (PDF) with coining the term WOZ method in 1980 to describe the research method he employed in his dissertation. However, Paula Roe credits Don Norman and Allan Munro for using the method as early as 1973 to conduct testing on an airport automated travel assistant. Regardless of who originated the method, both parties agree that it gained prominence when IBM later used it to conduct studies on a speech-to-text tool known as The Listening Typewriter (see Image below).

In this article, I’ll cover the core principles of the WOZ method, explore advanced applications taken from practical experience, and demonstrate its unique value through real-world examples, including its application to the field of agentic AI. UX practitioners can use the WOZ method as another tool to unlock user insights and craft human-centered products and experiences.

The Yellow Brick Road: Core Principles And Mechanics

The WOZ method operates on the premise that users believe they are interacting with an autonomous system while a human wizard manages the system’s responses behind the scenes. This individual, often positioned remotely (or off-screen), interprets user inputs and generates outputs that mimic the anticipated functionality of the experience.

Cast Of Characters

A successful WOZ study involves several key roles:

- The User

The participant who engages with what they perceive as the functional system. - The Facilitator

The researcher who guides the user through predefined tasks and observes their behavior and reactions. - The Wizard

The individual manipulates the system’s behavior in real-time, providing responses to user inputs. - The Observer (Optional)

An additional researcher who observes the session without direct interaction, allowing for a secondary perspective on user behavior.

Setting The Stage For Believability: Leaving Kansas Behind

Creating a convincing illusion is key to the success of a WOZ study. This necessitates careful planning of the research environment and the tasks users will undertake. Consider a study evaluating a new voice command system for smart home devices. The research setup might involve a physical mock-up of a smart speaker and predefined scenarios like “Play my favorite music” or “Dim the living room lights.” The wizard, listening remotely, would then trigger the appropriate responses (e.g., playing a song, verbally confirming the lights are dimmed).

Or perhaps it is a screen-based experience testing a new AI-powered chatbot. You have users entering commands into a text box, with another member of the product team providing responses simultaneously using a tool like Figma/Figjam, Miro, Mural, or other cloud-based software that allows multiple users to collaborate simultaneously (the author has no affiliation with any of the mentioned products).

The Art Of Illusion

Maintaining the illusion of a genuine system requires the following:

- Timely and Natural Responses

The wizard must react to user inputs with minimal delay and in a manner consistent with expected system behavior. Hesitation or unnatural phrasing can break the illusion. - Consistent System Logic

Responses should adhere to a predefined logic. For instance, if a user asks for the weather in a specific city, the wizard should consistently provide accurate information. - Handling the Unexpected

Users will inevitably deviate from planned paths. The wizard must possess the adaptability to respond plausibly to unforeseen inputs while preserving the perceived functionality.

Ethical Considerations

Transparency is crucial, even in a method that involves a degree of deception. Participants should always be debriefed after the session, with a clear explanation of the Wizard of Oz technique and the reasons for its use. Data privacy must be maintained as with any study, and participants should feel comfortable and respected throughout the process.

Distinguishing The Method

The WOZ method occupies a unique space within the UX research toolkit:

- Unlike usability testing, which evaluates existing interfaces, Wizard of Oz explores concepts before significant development.

- Distinct from A/B testing, which compares variations of a product’s design, WOZ assesses entirely new functionalities that might otherwise lack context if shown to users.

- Compared to traditional prototyping, which often involves static mockups, WOZ offers a dynamic and interactive experience, enabling observation of real-time user behavior with a simulated system.

This method proves particularly valuable when exploring truly novel interactions or complex systems where building a fully functional prototype is premature or resource-intensive. It allows researchers to answer fundamental questions about user needs and expectations before committing significant development efforts.

Let’s move beyond the foundational aspects of the WOZ method and explore some more advanced techniques and critical considerations that can elevate its effectiveness.

Time Savings: WOZ Versus Crude Prototyping

It’s a fair question to ask whether WOZ is truly a time-saver compared to even cruder prototyping methods like paper prototypes or static digital mockups.

While paper prototypes are incredibly fast to create and test for basic flow and layout, they fundamentally lack dynamic responsiveness. Static mockups offer visual fidelity but cannot simulate complex interactions or personalized outputs.

The true time-saving advantage of the WOZ emerges when testing novel, complex, or AI-driven concepts. It allows researchers to evaluate genuine user interactions and mental models in a seemingly live environment, collecting rich behavioral data that simpler prototypes cannot. This fidelity in simulating a dynamic experience, even with a human behind the curtain, often reveals critical usability or conceptual flaws far earlier and more comprehensively than purely static representations, ultimately preventing costly reworks down the development pipeline.

Additional Techniques And Considerations

While the core principle of the WOZ method is straightforward, its true power lies in nuanced application and thoughtful execution. Seasoned practitioners may leverage several advanced techniques to extract richer insights and address more complex research questions.

Iterative Wizardry

The WOZ method isn’t necessarily a one-off endeavor. Employing it in iterative cycles can yield significant benefits. Initial rounds might focus on broad concept validation and identifying fundamental user reactions. Subsequent iterations can then refine the simulated functionality based on previous findings.

For instance, after an initial study reveals user confusion with a particular interaction flow, the simulation can be adjusted, and a follow-up study can assess the impact of those changes. This iterative approach allows for a more agile and user-centered exploration of complex experiences.

Managing Complexity

Simulating complex systems can be difficult for one wizard. Breaking complex interactions into smaller, manageable steps is crucial. Consider researching a multi-step onboarding process for a new software application. Instead of one person trying to simulate the entire flow, different aspects could be handled sequentially or even by multiple team members coordinating their responses.

Clear communication protocols and well-defined responsibilities are essential in such scenarios to maintain a seamless user experience.

Measuring Success Beyond Observation

While qualitative observation is a cornerstone of the WOZ method, defining clear metrics can add a layer of rigor to the findings. These metrics should match research goals. For example, if the goal is to assess the intuitiveness of a new navigation pattern, you might track the number of times users express confusion or the time it takes them to complete specific tasks.

Combining these quantitative measures with qualitative insights provides a more comprehensive understanding of the user experience.

Integrating With Other Methods

The WOZ method isn’t an island. Its effectiveness can be amplified by integrating it with other research techniques. Preceding a WOZ study with user interviews can help establish a deeper understanding of user needs and mental models, informing the design of the simulated experience. Following a WOZ study, surveys can gather broader quantitative feedback on the concepts explored. For example, after observing users interact with a simulated AI-powered scheduling tool, a survey could gauge their overall trust and perceived usefulness of such a system.

When Not To Use WOZ

WOZ, as with all methods, has limitations. A few examples of scenarios where other methods would likely yield more reliable findings would be:

- Detailed Usability Testing

Humans acting as wizards cannot perfectly replicate the exact experience a user will encounter. WOZ is often best in the early stages, where prototypes are rough drafts, and your team is looking for guidance on a solution that is up for consideration. Testing on a more detailed wireframe or prototype would be preferable to WOZ when you have entered the detailed design phase. - Evaluating extremely complex systems with unpredictable outputs

If the system’s responses are extremely varied, require sophisticated real-time calculations that exceed human capacity, or are intended to be genuinely unpredictable, a human may struggle to simulate them convincingly and consistently. This can lead to fatigue, errors, or improvisations that don’t reflect the intended system, thereby compromising the validity of the findings.

Training And Preparedness

The wizard’s skill is critical to the method’s success. Training the individual(s) who will be simulating the system is essential. This training should cover:

- Understanding the Research Goals

The wizard needs to grasp what the research aims to uncover. - Consistency in Responses

Maintaining consistent behavior throughout the sessions is vital for user believability. - Anticipating User Actions

While improvisation is sometimes necessary, the wizard should be prepared for common user paths and potential deviations. - Remaining Unbiased

The wizard must avoid leading users or injecting their own opinions into the simulation. - Handling Unexpected Inputs

Clear protocols for dealing with unforeseen user actions should be established. This might involve having a set of pre-prepared fallback responses or a mechanism for quickly consulting with the facilitator.

All of this suggests the need for practice in advance of running the actual session. We shouldn’t forget to have a number of dry runs in which we ask our colleagues or those who are willing to assist to not only participate but also think about possible responses that could stump the wizard or throw things off if the user might provide them during a live session.

I suggest having a believable prepared error statement ready to go for when a user throws a curveball. A simple response from the wizard of “I’m sorry, I am unable to perform that task at this time” might be enough to move the session forward while also capturing a potentially unexpected situation your team can address in the final product design.

Was This All A Dream? The Art Of The Debrief

The debriefing session following the WOZ interaction is an additional opportunity to gather rich qualitative data. Beyond asking “What did you think?” effective debriefing involves sharing the purpose of the study and the fact that the experience was simulated.

Researchers should then conduct psychological probing to understand the reasons behind user behavior and reactions. Asking open-ended questions like “Why did you try that?” or “What were you expecting to happen when you clicked that button?” can reveal valuable insights into user mental models and expectations.

Exploring moments of confusion, frustration, or delight in detail can uncover key areas for design improvement. Think about the potential information the Power Gloves’ development team could have uncovered if they’d asked participants what the experience of programming the glove and trying to remember what they’d programmed into which set of keys had been.

Case Studies: Real-World Applications

The value of the WOZ method becomes apparent when examining its application in real-world research scenarios. Here is an in-depth review of one scenario and a quick summary of another study involving WOZ, where this technique proved invaluable in shaping user experiences.

Unraveling Agentic AI: Understanding User Mental Models

A significant challenge in the realm of emerging technologies lies in user comprehension. This was particularly evident when our team began exploring the potential of Agentic AI for enterprise HR software.

Agentic AI refers to artificial intelligence systems that can autonomously pursue goals by making decisions, taking actions, and adapting to changing environments with minimal human intervention. Unlike generative AI that primarily responds to direct commands or generates content, Agentic AI is designed to understand user intent, independently plan and execute multi-step tasks, and learn from its interactions to improve performance over time. These systems often combine multiple AI models and can reason through complex problems. For designers, this signifies a shift towards creating experiences where AI acts more like a proactive collaborator or assistant, capable of anticipating needs and taking the initiative to help users achieve their objectives rather than solely relying on explicit user instructions for every step.

Preliminary research, including surveys and initial interviews, suggested that many HR professionals, while intrigued by the concept of AI assistance, struggled to grasp the potential functionality and practical implications of truly agentic systems — those capable of autonomous action and proactive decision-making. We saw they had no reference point for what agentic AI was, even after we attempted relevant analogies to current examples.

Building a fully functional agentic AI prototype at this exploratory stage was impractical. The underlying algorithms and integrations were complex and time-consuming to develop. Moreover, we risked building a solution based on potentially flawed assumptions about user needs and understanding. The WOZ method offered a solution.

Setup

We designed a scenario where HR employees interacted with what they believed was an intelligent AI assistant capable of autonomously handling certain tasks. The facilitator presented users with a web interface where they could request assistance with tasks like “draft a personalized onboarding plan for a new marketing hire” or “identify employees who might benefit from proactive well-being resources based on recent activity.”

Behind the scenes, a designer acted as the wizard. Based on the user’s request and the (simulated) available data, the designer would craft a response that mimicked the output of an agentic AI. For the onboarding plan, this involved assembling pre-written templates and personalizing them with details provided by the user. For the well-being resource identification, the wizard would select a plausible list of employees based on the general indicators discussed in the scenario.

Crucially, the facilitator encouraged users to interact naturally, asking follow-up questions and exploring the system’s perceived capabilities. For instance, a user might ask, “Can the system also schedule the initial team introductions?” The wizard, guided by pre-defined rules and the overall research goals, would respond accordingly, perhaps with a “Yes, I can automatically propose meeting times based on everyone’s calendars” (again, simulated).

As recommended, we debriefed participants following each session. We began with transparency, explaining the simulation and that we had another live human posting the responses to the queries based on what the participant was saying. Open-ended questions explored initial reactions and envisioned use. Task-specific probing, like “Why did you expect that?” revealed underlying assumptions. We specifically addressed trust and control (“How much trust…? What level of control…?”). To understand mental models, we asked how users thought the “AI” worked. We also solicited improvement suggestions (“What features…?”).

By focusing on the “why” behind user actions and expectations, these debriefings provided rich qualitative data that directly informed subsequent design decisions, particularly around transparency, human oversight, and prioritizing specific, high-value use cases. We also had a research participant who understood agentic AI and could provide additional insight based on that understanding.

Key Insights

This WOZ study yielded several crucial insights into user mental models of agentic AI in an HR context:

- Overestimation of Capabilities

Some users initially attributed near-magical abilities to the “AI”, expecting it to understand highly nuanced or ambiguous requests without explicit instruction. This highlighted the need for clear communication about the system’s actual scope and limitations. - Trust and Control

A significant theme revolved around trust and control. Users expressed both excitement about the potential time savings and anxiety about relinquishing control over important HR processes. This indicated a need for design solutions that offered transparency into the AI’s decision-making and allowed for human oversight. - Value in Proactive Assistance

Users reacted positively to the AI proactively identifying potential issues (like burnout risk), but they emphasized the importance of the AI providing clear reasoning and allowing human HR professionals to review and approve any suggested actions. - Need for Tangible Examples

Abstract explanations of agentic AI were insufficient. Users gained a much clearer understanding through these simulated interactions with concrete tasks and outcomes.

Resulting Design Changes

Based on these findings, we made several key design decisions:

- Emphasis on Transparency

The user interface would need to clearly show the AI’s reasoning and the data it used to make decisions. - Human Oversight and Review

Built-in approval workflows would be essential for critical actions, ensuring HR professionals retain control. - Focus on Specific, High-Value Use Cases

Instead of trying to build a general-purpose agent, we prioritized specific use cases where agentic capabilities offered clear and demonstrable benefits. - Educational Onboarding

The product onboarding would include clear, tangible examples of the AI’s capabilities in action.

Exploring Voice Interaction for In-Car Systems

In another project, we used the WOZ method to evaluate user interaction with a voice interface for controlling in-car functions. Our research question focused on the naturalness and efficiency of voice commands for tasks like adjusting climate control, navigating to points of interest, and managing media playback.

We set up a car cabin simulator with a microphone and speakers. The wizard, located in an adjacent room, listened to the user’s voice commands and triggered the corresponding actions (simulated through visual changes on a display and audio feedback). This allowed us to identify ambiguous commands, areas of user frustration with voice recognition (even though it was human-powered), and preferences for different phrasing and interaction styles before investing in complex speech recognition technology.

These examples illustrate the versatility and power of the method in addressing a wide range of UX research questions across diverse product types and technological complexities. By simulating functionality, we can gain invaluable insights into user behavior and expectations early in the design process, leading to more user-centered and ultimately more successful products.

The Future of Wizardry: Adapting To Emerging Technologies

The WOZ method, far from being a relic of simpler technological times, retains relevance as we navigate increasingly sophisticated and often opaque emerging technologies.

The WOZ method’s core strength, the ability to simulate complex functionality with human ingenuity, makes it uniquely suited for exploring user interactions with systems that are still in their nascent stages.

“

WOZ In The Age Of AI

Consider the burgeoning field of AI-powered experiences. Researching user interaction with generative AI, for instance, can be effectively done through WOZ. A wizard could curate and present AI-generated content (text, images, code) in response to user prompts, allowing researchers to assess user perceptions of quality, relevance, and trust without needing a fully trained and integrated AI model.

Similarly, for personalized recommendation systems, a human could simulate the recommendations based on a user’s stated preferences and observed behavior, gathering valuable feedback on the perceived accuracy and helpfulness of such suggestions before algorithmic development.

Even autonomous systems, seemingly the antithesis of human control, can benefit from WOZ studies. By simulating the autonomous behavior in specific scenarios, researchers can explore user comfort levels, identify needs for explainability, and understand how users might want to interact with or override such systems.

Virtual And Augmented Reality

Immersive environments like virtual and augmented reality present new frontiers for user experience research. WOZ can be particularly powerful here.

Imagine testing a novel gesture-based interaction in VR. A researcher tracking the user’s hand movements could trigger corresponding virtual events, allowing for rapid iteration on the intuitiveness and comfort of these interactions without the complexities of fully programmed VR controls. Similarly, in AR, a wizard could remotely trigger the appearance and behavior of virtual objects overlaid onto the real world, gathering user feedback on their placement, relevance, and integration with the physical environment.

The Human Factor Remains Central

Despite the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence and immersive technologies, the fundamental principles of human-centered design remain as relevant as ever. Technology should serve human needs and enhance human capabilities.

The WOZ method inherently focuses on understanding user reactions and behaviors and acts as a crucial anchor in ensuring that technological progress aligns with human values and expectations.

“

It allows us to inject the “human factor” into the design process of even the most advanced technologies. Doing this may help ensure these innovations are not only technically feasible but also truly usable, desirable, and beneficial.

Conclusion

The WOZ method stands as a powerful and versatile tool in the UX researcher’s toolkit. The WOZ method’s ability to bypass limitations of early-stage development and directly elicit user feedback on conceptual experiences offers invaluable advantages. We’ve explored its core mechanics and covered ways of maximizing its impact. We’ve also examined its practical application through real-world case studies, including its crucial role in understanding user interaction with nascent technologies like agentic AI.

The strategic implementation of the WOZ method provides a potent means of de-risking product development. By validating assumptions, uncovering unexpected user behaviors, and identifying potential usability challenges early on, teams can avoid costly rework and build products that truly resonate with their intended audience.

I encourage all UX practitioners, digital product managers, and those who collaborate with research teams to consider incorporating the WOZ method into their research toolkit. Experiment with its application in diverse scenarios, adapt its techniques to your specific needs and don’t be afraid to have fun with it. Scarecrow costume optional.

(yk)

by Admin

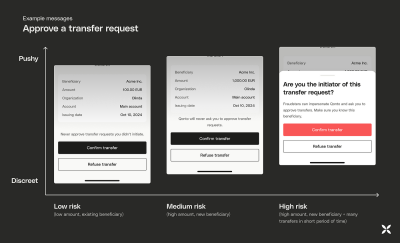

Design Guidelines For Better Notifications UX

Design Guidelines For Better Notifications UX Design Guidelines For Better Notifications UX Vitaly Friedman 2025-07-07T13:00:00+00:00 2025-07-09T15:33:43+00:00 In many products, setting notification channels on mute is a default, rather than an exception. The reason for that is their high frequency, which creates disruptions and eventually notification […]

Accessibility

Design Guidelines For Better Notifications UX

Vitaly Friedman 2025-07-07T13:00:00+00:00

2025-07-09T15:33:43+00:00

In many products, setting notification channels on mute is a default, rather than an exception. The reason for that is their high frequency, which creates disruptions and eventually notification fatigue, when any popping messages get dismissed instantly.

There is a good reason for it: high frequency of notifications. In usability testing, it’s the most frequent complaint, yet every app desperately tries to capture a glimpse of our attention, sending more notifications our way. Let’s see how we could make the notifications UX slightly better.

.course-intro{–shadow-color:206deg 31% 60%;background-color:#eaf6ff;border:1px solid #ecf4ff;box-shadow:0 .5px .6px hsl(var(–shadow-color) / .36),0 1.7px 1.9px -.8px hsl(var(–shadow-color) / .36),0 4.2px 4.7px -1.7px hsl(var(–shadow-color) / .36),.1px 10.3px 11.6px -2.5px hsl(var(–shadow-color) / .36);border-radius:11px;padding:1.35rem 1.65rem}@media (prefers-color-scheme:dark){.course-intro{–shadow-color:199deg 63% 6%;border-color:var(–block-separator-color,#244654);background-color:var(–accent-box-color,#19313c)}}

This article is part of our ongoing series on UX. You can find more details on design patterns and UX strategy in Smart Interface Design Patterns 🍣 — with live UX training coming up soon. Jump to table of contents.

The Many Faces Of Notifications

Notifications are distractions by nature; they bring a user’s attention to a (potentially) significant event they aren’t aware of or might want to be reminded of. As such, they can be very helpful and relevant, providing assistance and bringing structure and order to the daily routine. Until they are not.

Not every communication option is a notification. As Kim Salazar rightfully noted,

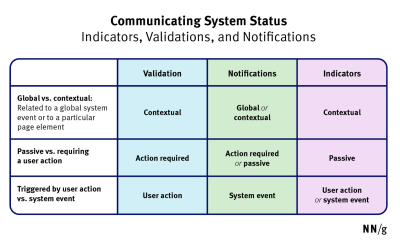

“Status communication often relies on validation, status indicators, and notifications. While they are often considered to be similar, they are actually quite different.”

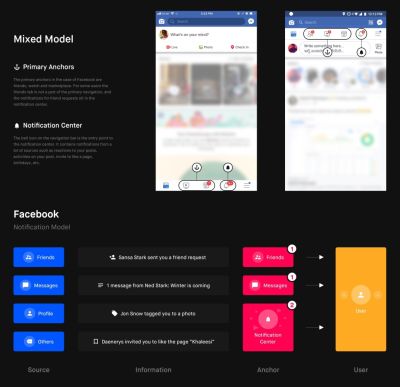

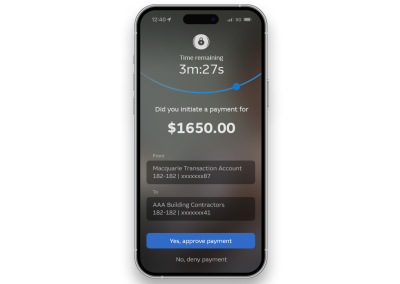

In general, notifications can be either informational (calendar reminders, delay notifications, election night results) or encourage action (approve payment, install an update, confirm a friend request). They can stream from various sources and have various impacts.

- UI notifications appear as subtle cards in UIs as users interact with the web interface — as such, they are widely accepted and less invasive than some of their counterparts.

- In-browser push notifications are more difficult to dismiss, and draw attention to themselves even if the user isn’t accessing the UI.

- In-app notifications live within desktop and mobile apps, and can be as humble as UI notifications, but can take a more central role with messages pushed to the home screen or the notifications center.

- OS notifications such as software updates or mobile carrier changes also get in the mix, often appearing together with a wide variety of notes, calendar updates, and everything in between.

- Finally, notifications can find their way into email, SMS, and social messaging apps, coming from chatbots, recommendation systems, and actual humans.

But we don’t pay the same amount of attention to every notification. It can take weeks until they eventually install a software update prompted by their OS notification, or just a few hours to confirm or decline a new LinkedIn request.

Not Every Notification Is Equal

The level of attention users grant to notifications depends on their nature, or, more specifically, how and when notifications are triggered. People care more about new messages from close friends and relatives, bank transactions and important alerts, calendar notifications, and any actionable and awaited confirmations or releases.

People care less about news updates, social feed updates, announcements, new features, crash reports, promotional and automated messages in general. Most importantly, a message from another human being is always valued much higher than any automated notification.

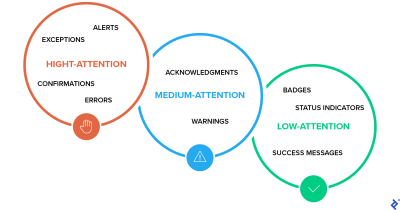

Design For Levels Of Severity

As Sara Vilas suggests, we can break down notification design across three levels of severity: high, medium, and low attention. And then, notification types need to be further defined by specific attributes on those three levels, whether they are alerts, warnings, confirmations, errors, success messages, or status indicators.

High Attention

- Alerts (immediate attention required),

- Errors (immediate action required),

- Exceptions (system anomalies, something didn’t work),

- Confirmations (potentially destructive actions that need user confirmation to proceed).

Medium Attention

- Warnings (no immediate action required),

- Acknowledgments (feedback on user actions),

- Success messages.

Low Attention

- Informational messages (aka passive notifications, something is ready to view),

- Badges (typically on icons, signifying something new since last interaction),

- Status indicators (system feedback).

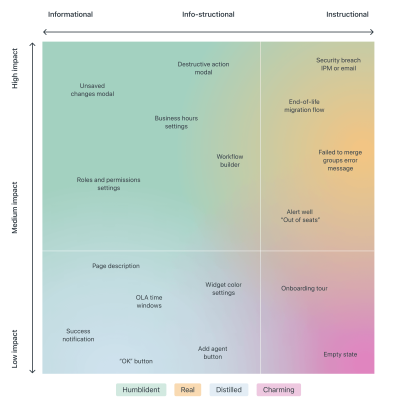

Taking it one step further, we can map the attention against the type of messaging we are providing — very similar to Zendesk’s mapping tone above, which plots impact against the type of messaging, and shows how the tone should adjust — becoming more humble, real, distilled or charming.

So, notifications can be different, and different notifications are perceived differently; however, the more personal, relevant, and timely notifications are, the higher engagement we should expect.

Start Sending Notifications Slowly But Steadily

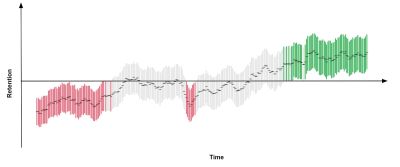

It’s not uncommon to sign up, only to realize a few moments later that the inbox is filling up with all kinds of irrelevant messages. That’s exactly the wrong thing to do. A study by Facebook showed that sending fewer notifications improved user satisfaction and long-term usage of a product.

Initially, once the notification rate was reduced, there was indeed a loss of traffic, but it has “gradually recovered over time”, and after an extended period, it had fully recovered and even turned out to be a gain.

A good starting point is to set up a slow default notification frequency for different types of customers. As the customer keeps using the interface, we could ask them to decide on the kind of notifications they’d prefer and their frequency.

Send notifications slowly, and over time slowly increase and/or decrease the number of notifications per type of customer. This might work much better for our retention rates.

Don’t Rely On Generic Defaults: Set Up Notification Modes

Typically, users can opt in and opt out of every single type of notification in their settings. In general, it’s a good idea, but it can also be very overwhelming — and not necessarily clear how important each notification is. Alternatively, we could provide predefined recommended options, perhaps with a “calm mode” (low frequency), a “regular mode” (medium frequency), and a “power-user mode” (high frequency).

As time passes, the format of notifications might need adjustments as well. Rather than having notifications sent one by one as events occur, users could choose a “summary mode,” with all notifications grouped into a single standalone message delivered at a particular time each day or every week.

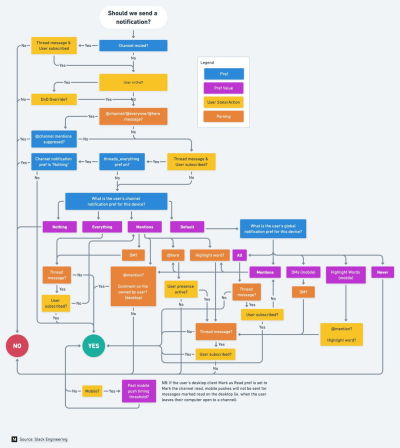

That’s one of the settings that Slack provides when it comes to notifications; in fact, the system adapts the frequency of notifications over time, too. Initially, as Slack channels can be quite silent, the system sends notifications for every posted message.

As activities become more frequent, Slack recommends reducing the notification level so the user will be notified only when they are actually mentioned.

Make Notification Settings A Part Of Onboarding

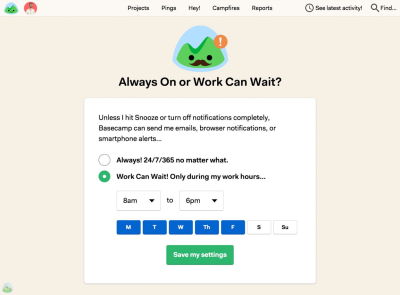

We could also include frequency options in our onboarding design. A while back Basecamp, for example, has introduced “Always On” and “Work Can Wait” options as a part of their onboarding, so new customers can select if they wish to receive notifications as they occur (at any time), or choose specific time ranges and days when notifications can be sent.

Or, the other way around, we could ask users when they don’t want to be disturbed, and suspend notifications at that time. Not every customer wants to receive work-related notifications outside of business hours or on the weekend, even if their colleagues might be working extra hours on Friday night on the other side of the planet.

Allow Users To Snooze Or Pause Notifications

User’s context changes continuously. If you notice an unusual drop in engagement rate, or if you’re anticipating an unusually high volume of notifications coming up (a birthday, wedding anniversary, or election night, perhaps), consider providing an option to mute, snooze, or pause notifications, perhaps for the next 24 hours.

This might go very much against our intuition, as we might want to re-engage the customer if they’ve gone silent all of a sudden, or we might want to maximize their engagement when important events are happening. However, it’s easy to reach a point when a seemingly harmless notification will steer a customer away, long term.

Another option would be to suggest a change of medium used to consume notifications. Users tend to associate different levels of urgency with different channels of communication.

In-app notifications, push notifications, and text messages are considered to be much more intrusive than good ol’ email, so when frequency exceeds a certain threshold, you might want to nudge users towards a switch from push notifications to daily email summaries.

Wrapping Up

As always in design, timing matters, and so do timely notifications. Start slowly, and evolve your notification frequency depending on how exactly a user actually uses the product. For every type of user, set up notification profiles: frequent users, infrequent users, one-week-experience users, one-month-experience users, and so on.

And whenever possible, allow your users to snooze and mute notifications for a while. Eventually, you might even want to suggest a change in the medium used to consume notifications. And when in doubt, postpone, rather than sending through.

Meet “Smart Interface Design Patterns”

You can find more details on design patterns and UX in Smart Interface Design Patterns, our 15h-video course with 100s of practical examples from real-life projects — with a live UX training later this year. Everything from mega-dropdowns to complex enterprise tables — with 5 new segments added every year. Jump to a free preview. Use code BIRDIE to save 15% off.

Video + UX Training

$ 495.00 $ 699.00

Get Video + UX Training

25 video lessons (15h) + Live UX Training.

100 days money-back-guarantee.

Video only

$ 300.00$ 395.00

40 video lessons (15h). Updated yearly.

Also available as a UX Bundle with 2 video courses.

(yk)

by Admin

Turning User Research Into Real Organizational Change

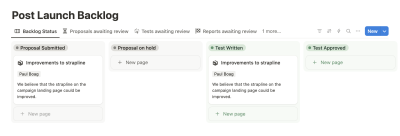

Turning User Research Into Real Organizational Change Turning User Research Into Real Organizational Change Paul Boag 2025-07-01T10:00:00+00:00 2025-07-02T15:03:33+00:00 This article is sponsored by Lyssna We’ve all been there: you pour your heart and soul into conducting meticulous user research. You gather insightful data, create detailed […]

Accessibility

Turning User Research Into Real Organizational Change

Paul Boag 2025-07-01T10:00:00+00:00

2025-07-02T15:03:33+00:00

This article is sponsored by Lyssna

We’ve all been there: you pour your heart and soul into conducting meticulous user research. You gather insightful data, create detailed reports, and confidently deliver your findings. Yet, months later, little has changed. Your research sits idle on someone’s desk, gathering digital dust. It feels frustrating, like carefully preparing a fantastic meal, only to have it left uneaten.

There are so many useful tools (like Lysnna) to help us run incredible user research, and articles about how to get the most from them. However, there’s much less guidance about ensuring our user research gets adopted and brings about real change. So, in this post, I want to answer a simple question: How can you make sure your user research truly transforms your organization?

Introduction

User research is only as valuable as the impact it has.

When research insights fail to make their way into decisions, teams miss out on opportunities to improve products, experiences, and ultimately, business results. In this post, we’ll look at:

- Why research often fails to influence organizational change;

- How to ensure strategic alignment so research matters from day one;

- Ways to communicate insights clearly so stakeholders stay engaged;

- How to overcome practical implementation barriers;

- Strategies for realigning policies and culture to support research-driven changes.

By covering each of these areas, you’ll have a clear roadmap for turning your hard-won research into genuine action.

Typical Reasons For Failure

If you’ve ever felt your research get stuck, it probably came down to one (or more) of these issues.

Strategic Misalignment

When findings aren’t tied to business objectives or ROI, they struggle to gain traction. Sharing a particular hurdle that users face will fall on deaf ears if stakeholders cannot see how that problem will impact their bottom line.

Research arriving too late is another hurdle. If you share insights after key decisions are made, stakeholders assume your input won’t change anything. Finally, research often competes with other priorities. Teams might have limited resources and focus on urgent deadlines rather than long-term user improvements.

Communication Issues

Even brilliant research can get lost in translation if it’s buried in dense reports. I’ve seen stakeholders glaze over when handed 30-page documents full of jargon. When key takeaways aren’t crystal clear, decision-makers can’t quickly act on your findings.

Organizational silos can make communication worse. Marketing might have valuable insights that product managers never see, or designers may share findings that customer support doesn’t know how to use. Without a way to bridge those gaps, research lives in a vacuum.

Implementation Challenges

Great insights require a champion. Without a clear owner, research often lives with the person who ran it, and no one else feels responsible. Stakeholder skepticism also plays a role. Some teams doubt the methods or worry the findings don’t apply to real customers.

Even if there is momentum, insufficient follow-up or progress tracking can stall things. I’ve heard teams say, “We started down that path but ran out of time.” Without regular check-ins, good ideas fade away.

Policy And Cultural Barriers

Legal, compliance, or tech constraints can limit what you propose. I once suggested a redesign to comply with new accessibility standards, but the existing technical stack couldn’t support it. Resistance due to established culture is also common. If a company’s used to launching fast and iterating later, they might see research-driven change as slowing them down.

Now that we understand what stands in the way of effective research implementation, let’s explore practical solutions to overcome these challenges and drive real organizational change.

Ensuring Strategic Alignment

When research ties directly to business goals, it becomes impossible to ignore. Here’s how to do it.

Early Stakeholder Engagement

Invite key decision-makers into the research planning phase. I like to host a kickoff session where we map research objectives to specific KPIs, like increasing conversions by 10% or reducing support tickets by 20%. When your stakeholders help shape those objectives, they’re more invested in the results.

Research Objectives Aligned With Business KPIs

While UX designers often focus on user metrics like satisfaction scores or task completion rates, it’s crucial to connect our research to business outcomes that matter to stakeholders. Start by identifying the key business metrics that will demonstrate the value of your research:

- Identify which metrics matter most to the organization (e.g., conversion rate, churn, average order value).

- Frame research questions to directly address those metrics.

- Make preliminary hypotheses about how insights may affect the bottom line.

Develop Stakeholder-Specific Value Propositions

When presenting user research to groups, it’s easy to fall into the trap of delivering a one-size-fits-all message that fails to truly resonate with anyone. Instead, we need to carefully consider how different stakeholders will receive and act on our findings.

The real power of user research emerges when we can connect our insights directly to what matters most for each specific audience:

- For the product team: Show how insights can reduce development time by eliminating guesswork.

- For marketing: Demonstrate how understanding user language can boost ad copy effectiveness.

- For executives: Highlight potential cost savings or revenue gains.

ROI Framework Development

Stakeholders want to see real numbers. Develop simple templates to estimate potential cost savings or revenue gains. For example, if you uncover a usability issue that’s causing a 5% drop-off in the signup flow, translate that into lost revenue per month.

I also recommend documenting success stories from similar projects within your own organization or from case studies. When a stakeholder sees that another company boosted revenue by 15% after addressing a UX flaw, they’re more likely to pay attention.

Research Pipeline Integration

Integrate research tasks directly into your product roadmap. Schedule user interviews or usability tests just before major feature sprints. That way, findings land at the right moment — when teams are making critical decisions.

Regular Touchpoints with Strategic Teams

It’s essential to maintain consistent communication with strategic teams through regular research review meetings. These sessions provide a dedicated space to discuss new insights and findings. To keep everyone aligned, stakeholders should have access to a shared calendar that clearly marks key research milestones. Using collaborative tools like Trello boards or shared calendars ensures the entire team stays informed about the research plan and progress.

Resource Optimization

Research doesn’t have to be a massive, months-long effort each time. Build modular research plans that can scale. If you need quick, early feedback, run a five-user usability test rather than a full survey. For deeper analysis, you can add more participants later.

Addressing Communication Issues

Making research understandable is almost as important as the research itself. Let’s explore how to share insights so they stick.

Create Research One-Pagers

Condense key findings into a scannable one-pager. No more than a single sheet. Start with a brief summary of the problem, then highlight three to five top takeaways. Use bold headings and visual elements (charts, icons) to draw attention.

Implement Progressive Disclosure

Avoid dumping all details at once. Start with a high-level executive summary that anyone can read in 30 seconds. Then, link to a more detailed section for folks who want the full methodology or raw data. This layered approach helps different stakeholders absorb information at their own pace.

Use Visual Storytelling

Humans are wired to respond to stories. Transform data into a narrative by using journey maps, before/after scenarios, and user stories. For example, illustrate how a user feels at each step of a signup process, then show how proposed changes could improve their experience.

Regular Stakeholder Updates

Keep the conversation going. Schedule brief weekly or biweekly “research highlights” emails or meetings. These should be no more than five minutes and focus on one or two new insights. When stakeholders hear snippets of progress regularly, research stays top of mind.

Interactive Presentations

Take research readouts beyond slide decks. Host workshop-style sessions where stakeholders engage with findings hands-on. For instance, break them into small groups to discuss a specific persona and brainstorm solutions. When people physically interact with research (sticky notes, printed journey maps), they internalize it better.

Overcome Implementation Challenges

Now that stakeholders understand and value your research, let’s make sure they turn insights into action.

Establish Clear Ownership

Assign a dedicated owner for each major recommendation. Use a RACI matrix to clarify who’s Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed. I like to share a simple table listing each initiative, the person driving it, and key milestones.

When everyone knows who’s accountable, progress is more likely.

RACI Matrix Example

| Initiative | Responsible | Accountable | Consulted | Informed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Redesign Signup Flow | UX Lead | Product Manager | Engineering, Legal | Marketing, Support |

| Create One-Pager Templates | UX Researcher | Design Director | Stakeholder Team | All Departments |

Build Implementation Roadmaps

Break recommendations down into phases. For example,

- Phase 1: Quick usability tweaks (1–2 weeks).

- Phase 2: Prototype new design (3–4 weeks).

- Phase 3: Launch A/B test (2–3 weeks).

Each phase needs clear timelines, success metrics, and resources identified upfront.

Address Stakeholder Skepticism

Be transparent about your methods. Share your recruitment screeners, interview scripts, and a summary of analysis steps. Offer validation sessions where stakeholders can ask questions about how the data was collected and interpreted. When they understand the process, they trust the findings more.

Create Support Systems

Even when stakeholders agree, they need help executing. Establish mentorship or buddy programs where experienced researchers or designers guide implementation. Develop training materials, like short “how-to” guides on running usability tests or interpreting survey data. Set up feedback channels (Slack channels, shared docs) where teams can ask questions or share roadblocks.

Monitor And Track Progress

Establish regular progress reviews weekly or biweekly. Use dashboards to track metrics such as A/B test performance, error rates, or user satisfaction scores. Even a more complicated dashboard can be built using no-code tools and AI, so you no longer need to rely on developer support.

Realign Policies and Culture

Even the best strategic plans and communication tactics can stumble if policies and culture aren’t supportive. Here’s how to address systemic barriers.

Create a Policy Evolution Framework

First, audit existing policies for anything that blocks research-driven changes. Maybe your data security policy requires months of legal review before you can recruit participants. Document those barriers and work with legal or compliance teams to create flexible guidelines. Develop a process for policy exception requests — so if you need a faster path for a small study, you know how to get approval without massive delays.

Technical Infrastructure Adaptation

Technology can be a silent killer of good ideas. Before proposing changes, work with IT to understand current limitations. Document technical requirements clearly so teams know what’s feasible. Propose a phased approach to any necessary infrastructure updates. Start with small changes that have an immediate impact, then plan for larger upgrades over time.

Build Cultural Buy-In

Culture shift doesn’t happen overnight. Share quick wins and success stories from early adopters in your organization. Recognize and reward change pioneers. Send a team-wide shout-out when someone successfully implements a research-driven improvement. Create a champions network across departments, so each area has at least one advocate who can spread best practices and encourage others.

Develop a Change Management Strategy

Change management is about clear, consistent communication. Develop tailored communication plans for different stakeholder groups. For example, executives might get a one-page impact summary, while developers get technical documentation and staging environments to test new designs. Establish feedback channels so teams can voice concerns or suggestions. Finally, provide change management training for team leaders so they can guide their direct reports through transitions.

Measure Cultural Impact

Culture can be hard to quantify, but simple pulse surveys go a long way. Ask employees how they feel about recent changes and whether they are more confident using data to make decisions. Track employee engagement metrics like survey participation or forum activity in research channels. Monitor resistance patterns (e.g., repeated delays or rejections) and address the root causes proactively.

Conclusions

Transforming user research into organizational change requires a holistic approach. Here’s what matters most:

- Strategic Alignment: Involve stakeholders early, tie research to KPIs, and integrate research into decision cycles.

- Effective Communication: Use one-pagers, progressive disclosure, visual storytelling, regular updates, and interactive presentations to keep research alive.

- Implementation Frameworks: Assign clear ownership, build phased roadmaps, address skepticism, offer support systems, and track progress.